Resumen

Índice

- Key Ideas

- Basic Skills to get quality data

- Identifying and completing the data. When questioning is appropriate: Skills during the history taking

- Basic techniques to get real, reliable and valid data

- The importance of taking a focussed history. Chronology and associated symptoms.

- Summary of information obtained.

- Physical examination, if appropriate

- Practical example: a 'broken' patient

- Mistakes to avoid

- Intuitive interviewers and field dependence

- Focalised interviewers

- Blocking patients and interviewers who ask a lot but... by using close questions!

- Skimming too quickly over the psychological aspects

- Situations Gallery

- The vague patient

- Difficulties getting into the psychosocial aspects

- Starting from scratch!

- Pelvic examination

- Taking a history of sexual behaviour and risk assessment

- Advanced Concepts

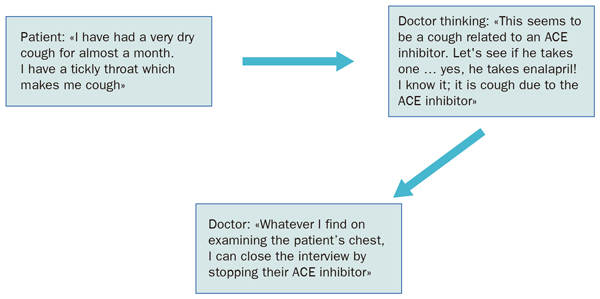

- Drawings in the mind

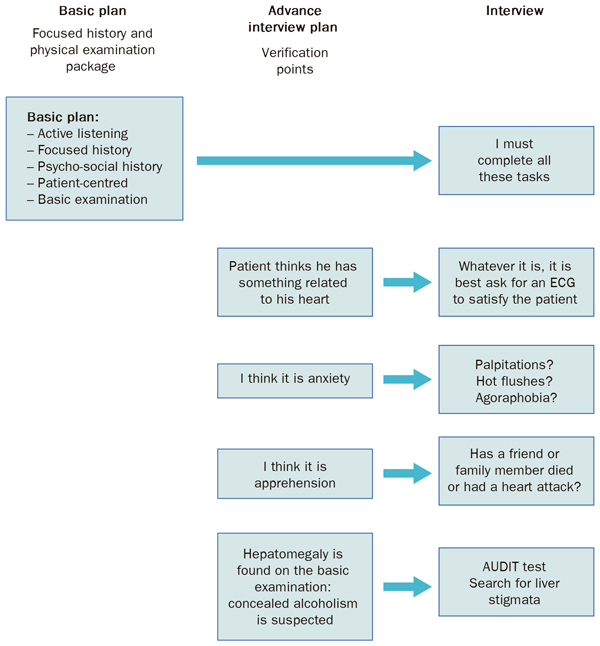

- Basic and advanced interview plan

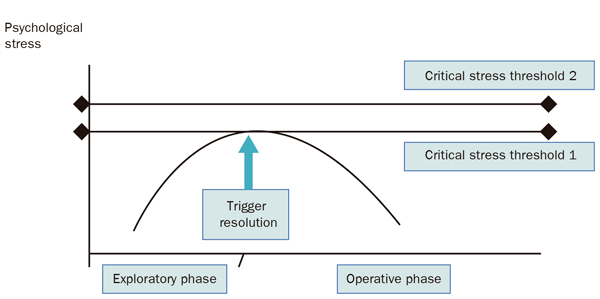

- Three difficulties in interpreting and formulating clinical data. Concept of critical stress

- Making sense of the patient's story. The conditions which are sufficient to enable a diagnosis.

- Anchoring the diagnosis

- Thought by criteria versus intuitive thought

- A first approach to the decision rules (heuristics).

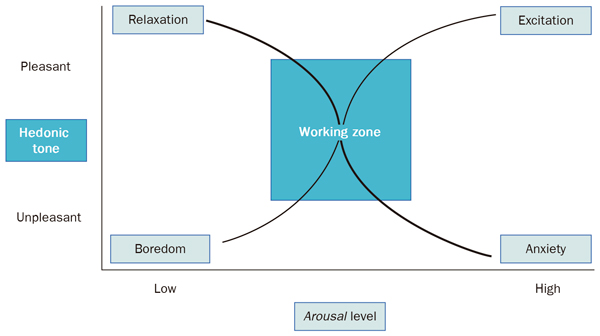

- Optimal regulation of the working zone

- Insurance expertise

- The depth of a diagnosis, the diagnostic statement and the biopsychosocial model

- Summary

- Bibliography

Good quality data for making good diagnoses

Key Ideas

-

Patients do not have any obligation to be the good patients that practitioners want.

-

We give more value to strategies to simplify and shorten the interview time, than strategies which minimise the risk of clinical error.

-

The history taking should not end until the clinician is able to write a report specifying, at least, the chronology and nature of the problem.

-

History taking by pathographic viewing: chronology (film of events), plot (soundtrack, what happens), impact (relieving factors).

-

We need to automate groups of questions, depending on the clinical situation, so it hardly requires us any effort to put them into practice, in particular what we call the 'psychosocial jump'.

-

The physical examination is part of the interpersonal relationship and it begins when a patient enters the consulting room. By listening and observing, we are already examining the patient.

-

We must know our tolerance to 'uncertainty' (critical strain), and the pressure that patients sometimes put us under ('to heal me!'), to give ourselves more time and not to prematurely finish the consultation.

-

Pathology of frequent attendance: 'you come so often, I often disregard you'.

-

Starting from scratch with a frequently attending patient is a true exercise of humility!

-

Being careful in formulating a diagnosis gives us the freedom to modify it more easily in the future.

-

What is the main bioethical challenge of a clinician? getting up from the chair to assess patients over and over again!

Basic Skills to get quality data

Watching is to set our sight on something, listening is to attend, but understanding is not only being attentive, but it has some recreation. The clinician who can understand endorses the patient's materials, plays them in their own imagination and recreates them, as if they were partly their own experiences. We found that a good clinician is someone who before understanding others has understood, has explored and has heard himself. Anyone who claims to know something about the world by only projecting what they have heard or read is delusional! We can only glimpse the world, the patient, and others in general, through our experiences. Our body and our own emotions are the filter, and the inescapable musical instrument to internalise and understand others. We have an image of the patient which we compare with similar images of the patient and we internalise this and interpret it with our own emotions: 'how would I feel if...?' We have a deeper understanding of the patient at this point and this process enables us to understand and share the patient’s experiences and emotions i.e. to empathise. One of the keys to intuitive thinking may lie within this; internalising by analogy. But that is not all; the clinician does not renounce the semiological data which is an objective analysis, is purely external and is based on well-established criteria. In order to listen in a semiological manner we must acquire very complex practices. We will devote this chapter to this. Give us good data, allow ourselves to go beyond our first impressions and allow our intelligence to work. We will defend a concept of expertise based on a continued contrast between intuitive thought and thought based on criteria.

All that will be taken care of in this chapter, in which we take the semi-structured interview for the exploratory part as a starting point. Remember that the tasks are:

-

Review the patient's past medical history or the patient’s previous consultations in their medical records.

-

Warm greeting.

-

Establishing the presenting complaint. Map of demands and complaints. Pathobiography

-

Active listening ('the interview leak point')

-

Find and complete data.

-

Summary of the information obtained.

-

Physical examination, if any.

In Chapter 2 we reached the fourth point, and in this chapter we will address items 5, 6 and 7, with an emphasis on semiologic skills, through the sphere of the rational-emotive model of the clinical act

Identifying and completing the data. When questioning is appropriate: Skills during the history taking

Any interviewer should effortlessly use four packages of questions (Table 3.1).

|

Table 3.1. The four packages of questions for history taking |

|

|

First package: active listening skills |

|

|

Technical types |

When it becomes necessary |

|

Showing interest |

When we are interested in viewing the world and the patient's experiences without influencing the narration of the facts |

|

Facilitators |

Very useful at the beginning of the interview |

|

Phrases by repetition |

When the presenting complaint is unclear |

|

Empathy |

When it appears that the patient wants to entrust us with 'sensitive material' |

|

Suggested addition technique |

When the patient finds it difficult to talk |

|

Second package: questions for taking a focussed history |

|

|

|

|

|

How is your pain |

|

|

When did the pain start and chronology of their pain |

When we want to establish facts regarding their symptoms |

|

Where does it radiate |

The presenting complaint is very clear |

|

What makes the pain better or worse |

There is a symptom or sign guide |

|

Associated symptoms |

|

|

Risk factors |

|

|

Third package: questions for taking a psychosocial history |

|

|

Question type |

When it becomes necessary |

|

What is your sleep like? |

When we want to establish the psychological impact of the patient's discomfort |

|

How is your mood? |

When we suspect psychosocial stress or psychological difficulties |

|

Do you have any concerns or worries? |

There are many mottled symptoms in the patient's narrative The patient who consults very frequently |

|

Do you have any serious problems at work or at home? |

The patient gives clues that guide us to this area |

|

Fourth package: questions for a patient-centred interview |

|

|

Question type |

When it becomes necessary |

|

What are your ideas about your symptoms? |

We want to know the impact of the illness on the patient. |

|

How are things affecting your life? |

When the patient expresses concern, gloominess or anger. |

|

How Do you think we can help you? What should we do to improve the situation? something which they don't quite express |

When we have the impression that the patient wants |

|

Has something happened that Has changed your life? Or Has something happened that Has had a big impact on you? |

|

|

Any are there any problems at home Or at work |

We suspect problems in the home which are affecting you? or work environment |

These packages are to be learned in such way that they then arise almost naturally. How do we know whether we have grasped these techniques properly? Here are some indicators:

Active listening package

An indicator that this package of skills has borne its fruit is that the patient starts to talk in a more open way, providing longer answers. We have already spoken of this package in Chapter 2, so we will not expand here.

Package for focused histories

An indicator that this package of skills has borne fruit is that we have enough data to be able to write a clinical report with the features and chronology of the patient's symptoms. The patient considers the history taking to be the specific part of the healing art and that the Doctor will diagnose them with just the history taking. However, sometimes the clinician does this it in an incomplete way, as we will see later.

Package for the psychosocial history

A mistake is to think that this package should be activated only when the patient presents with psychological problems or problems with the social or family environment. In fact, every patient with chronic pain, patients who attend very often or patients with vague symptoms, can benefit from a psychosocial assessment. An indicator that this package bears fruit is that we can outline elements of stress or emotional aspects of the patient. It is important to distinguish a real resistance to talk about psychosocial issues ('I’d prefer not to talk about this topic'), fear that we relate the patient's symptoms to this area ('everybody says that this is anxiety and I don’t think this is anxiety at all'). In the latter case, we can try to prevent this resistance to talking about psychosocial issues by starting with a focussed history and, before making the jump to the psychosocial aspects, with sign posting by saying something like: 'well, now I would like to find out a bit more about you as a person... 'Do you have any hobbies? Which ones?... and do you sleep well?... how is your mood?», etc. Another strategy to start talking about psychosocial issues is to find out the quality of their sleep. On the other hand, it would be a mistake to ask: 'and what about your anxiety?’

A patient-centred package

It is a package which is not usually activated at first, as it could lead to some confusion. Sometimes we ask the patient: 'what do you think is happening to you?' And the patient answers: 'I don't know; that is why I have come to see you'. We name this response as the boomerang effect, and it should be followed with: ‘yes, of course, but I would like to know your opinion, what you think about it or what you might have discussed with your friends or family about this' (returning the boomerang). One indicator that this package is properly applied is that the flow of communication with the patient improves.

The big challenge for this part of the interview is to collect quality data. It is important that this data is real data, effectively sensed or experienced by the patient; reliable, meaning, that if another interviewer asks they will get similar responses, and valid, meaning, the data collected should be the data we are trying to obtain. In other words:

-

Real data: this patient... tells me things that have indeed happened?

-

Reliable data: another interviewer ... will they get similar answers?

-

Valid data: Is the data I am trying to obtain to get a diagnosis, useful for this patient and this clinical situation?

Basic techniques to get real, reliable and valid data

The most important thing is to create an atmosphere focused on the patient, avoiding 'yes' or 'no' questions almost automatically. In general, the more detail provided, the more realistic and reliable the data.

A concentration of closed questions diminishes the appearance of care focused on the patient. For example:

I: Does it happen more often in the morning?

P: Yes.

I: And when it happens, do you feel sick?

P: Yes.

I: Have you ever seen blood in your vomit?

P: No, no...

Here we see closed questions which can be answered in monosyllables. The risk of the patient responding 'to please' the interviewer is very high. If one of the answers has gone against the interviewer’s ‘expectation’, for example: 'now that you mention it, I once saw some blood, yes...’ this will undoubtedly have great diagnostic value.

Conversely, open questions require some verbalisation. Unlike closed questions, they cannot be answered monosyllabically. Some examples would be: 'how is the pain?’, ‘what were you doing when the pain started?' etc. We must avoid mistakes by adding a postscript which 'closes' the question; for example 'how is the pain? Is it stabbing?', so the question becomes a closed question. Do not forget the juxtaposition of techniques principle, discussed above, whereby when two techniques are juxtaposed, the one used last is always the predominant one, in this case, the closed question.

It is also a mistake to rush to start asking closed questions without first offering a ‘menu’ of suggested responses. A menu of suggested responses means offering 'clues' indicating the type of response expected. For example: 'Is the pain sharp, like a bite or as if someone is squeezing you?', ' did it happen years, days or months ago?' etc.

The menu of suggestions doesn't have to advise the patient about what we view as the most logical or plausible response. If, for example, we say: 'Has this been happening for months or for days?' we are implying that we expect the problem to have been happening for a short period of time and we would not accept: 'no, it is been going on for many years' as a consistent answer. For this reason, we prefer an illogical sequence of suggested answers such as: 'years, days or months?'

Another common mistake is to formulate a menu of suggestions that remains as only a single suggestion, either because we cannot think of more, or because when going to mention the second suggestion, the patient interrupts and says: 'yes, it is exactly as you’ve just said'. In both cases, we will reformulate the menu, in order to verify that, the patient indeed meant what they said.

Closed questions are those which we use most often. The value of the information they provide is very variable, depending on the degree of suggestibility of the patient and whether we use other techniques to check the validity of the information'. But sometimes we can't avoid them, especially when we are interested in a very specific aspect of the history. Its formulation is obvious: 'Does it happen in the morning?', 'Does it hurt here?' etc.

Such questions have to be complemented with open questions and the menu of suggestions. It is useful to follow a positive answer from the patient to a closed question with an open question. For example, if we ask: 'do you have a burning sensation when passing urine?' and the patient answers: 'yes, I do’, it would be appropriate to confirm this information by asking for some more information 'could you tell me more about that?'. If you tend to ask closed questions, you can easily transform them into 'a menu of suggestions’ adding '...or perhaps the opposite?’ For example, 'does it hurt before eating...or after eating? Is the pain in your stomach...or in other parts of your tummy?’ The resulting sentences won't be included in the annals of the Royal College, but the final effect is appropriate for the purpose that we pursue: avoiding mechanical 'yes and no answers'.

Even more dangerous are the induced response questions. For example, the professional says:

-

I assume you have not had chest pain here, right?

-

Yeah, but basically you seem cheerful, don't you?

-

I assume you have never vomited blood, have you?

Instead, open questions with specific content have clear advantages. Observe, in the first example, an interviewer with no special skills, and the same patient in hands of a skilled interviewer.

Interview with a novice

P: You insist this is depression, but I have continued pains and they don't disappear, I am suffering. And I have so much to do at home!

I: Are you tearful?

P: Of course I am. This is due to how I see myself.

I: Does your husband help you?

P: My husband has a lot of work. He gets up at 6 am and he doesn't come back until dinner time.

I: But, do you have a good relationship with your husband? Do you communicate well?

P: He is bored with my complaints, as you can imagine.

Interview with an expert

/1/ P: You insist this is depression, but I have continued pains and they don't disappear, I am suffering. And I have so much to do at home!

/2/ I (showing some empathy): I see... (Accompanying the transition): We will come back to your pain. Now, I would like to discuss another topic, for me to get to know you better, (open question): what do you do when you are alone?

/3/ P: I like listening to music. I used to dance when I was home alone (laughing). I used to go out with some friends for a walk and we used to have a coffee in the park.

/4/ I (showing some empathy): That is fine. (Open question): And when your husband comes back home, what does he usually do?

/5/ P: He has a shower and we have dinner.

/6/ I (closed questions): Do you talk while having dinner?

/7/ P: We watch TV. It is the only time of day we can watch sport.

/8/ I (confirmatory sentence): Of course, do you also enjoy watching football?

/9/ P: No, I don't like it at all, but what can I do?

/10/ I (open question with behavioural signalling value): And at night, what type of person is your husband?

/11/ P: He goes about his business, he does as he pleases, you understand ...

/12/ I (closed question): Do you mean if he wants to make use of your marital relationship?

/13/ P: Yes...

/14/ I (confirmatory sentence ): But you do not want to do so.

/15/ P (looking down): No ...

/16/ I (closed question with emotional signalling value): Have you ever been afraid of him?

The patient begins to cry, and from this point the clinician can establish a picture of domestic abuse.

Note the use of closed and inconclusive questions from the first interviewer versus a more open technique from the second interviewer but, at the same time the second interview contains a very specific content. In particular we can point out from the second interview the following interventions:

/2/I (showing some empathy): I see... (Accompanying the transition): We will come back to your pain. Now, I would like to discuss another topic, for me to get to know you better, (open question): what do you do when you are alone?

With this intervention the interviewer cleaves the patient’s reality into two levels: the level of complaints, which he promises to come back to later, and the level of everyday life, which shifts the focus of attention. Thus, he manages to lower the defences of the patient and gets into the social aspects by talking about her hobbies. The following questions or interventions are also very specific, getting the interviewer literally into the patient's reality. He wants to see what happens and the feelings that the patient has in these circumstances. We recommend to the reader that it is this effort to see what is happening, more than a particular technique, which guides the interviewer. All this allows him to say:

/10/ I: And at night, what type of person is your husband?

This is an open question, but a very specific one and with a well defined symbolic content. Thus, we should add that it has a behavioural signalling value and possibly emotional signalling because ultimately, it will make the patient think about her emotional and sexual relationships. It would have also been appropriate to ask questions like: Is he affectionate towards you, for example does he hug you? Does he say loving things? Etc. Finally, to get into the topic of domestic abuse:

/16/ I: Have you ever been afraid of him?

This question is a true 'trump', of high performance. In table 3.2 we summarise other 'aces' indicating the clinical settings in which they can be used.

Other ways to get enquire about marital relations: 'Is it a pleasant relationship? Have you ever felt that his comments hurt you?'. Note that in all situations in Table 3.2, it is essential to draw a picture with concrete data of the patient's reality (The pathographic display technique, which we will talk about later)

|

Table 3.2 Trumps |

|

|

Intervention Have you ever thought about harming yourself? Has a family member (or your partner) ever complained about your alcohol intake? It is easy to miss taking your tablets, has this happened to you? What type of person is your husband at night? Have you ever felt scared of him? |

Clinical context A suspicion of suicidal ideation Alcohol misuse suspected We suspect poor adherence to medication Sexual problems suspected A suspicion of domestic abuse |

The importance of taking a focussed history. Chronology and associated symptoms.

Work on evaluation of clinical competence highlighted a deficit in taking a focussed history and doing a physical examination (Sunol R, 1992, Barragan N, 2000, Borrell C, 1990; Prados JA, 2003). Even experienced clinicians take for granted too much data. They don't find out the chronology of events in sufficient detail, and don't look for associated symptoms. This in part is due to a lack of time. We give more value to simplifying interview strategies than strategies that minimise the risk of a clinical error.

We have mentioned that focused history taking does not end until the clinician is able to write a report detailing the onset of the symptoms, the nature of the symptoms and the variation of the symptoms over time, trigger factors which worsen or improve the symptom, and any associated symptoms.

Any objective data (signs) or subjective data (symptoms) can lead to the diagnosis, we mean; it can become a guide symptom or sign. Let's see some technical aspects necessary to obtain quality data with the method we call pathographic display:

- Chronology (film of events). The inexperienced clinician usually finds out in detail the quality of the symptom(s). But they often forget the chronology or the timeline of events: when it started, whether it was intermittent and if there were intervals with no symptoms, if it has happened before, if it is improving or worsening. However finding the film of the facts is invaluable. A headache that lasts three months and gradually becomes worse to the point of disturbing sleep should alert us. Be precise: a date is better than 'weeks'. Be thorough: Is always the same intensity? Do you have asymptomatic intervals? Etc.

- Plot (soundtrack). Knowing the film of events we are going to add the soundtrack. What is your pain like? How strong is it? Where is it? Does it radiate anywhere? As we said previously, we will move from open questions to the menu of suggestions and finally to closed questions (Figure 3.1). For example, when we ask about a headache it is preferential to ask: ‘please can you point to the area of your head which hurts most' to 'does it hurt here? (Pointing to a specific part). If, for example, we say: 'does the entire head hurt (emphasising it) or just here?’ the patient could understand, at a non-verbal level, that we expect to be 'all' of their head. It would be, therefore, a question with an induced response. We will invite the patient to locate the discomfort in their body, preferring to point an area than a verbal reference. Occasionally, we will ask the patient to describe whether the discomfort is superficial or deep, and if 'it goes anywhere else', a sentence that is better understood that the word 'radiation'. We will always try to avoid medical jargon such as 'dyspepsia', 'gastritis', ‘migraine’, even if we think the patient will understand it.

- Biographic impact (relieving factors). And now we need to find out the relieving factors. This is of vital importance in relation to the symptoms, factors that exacerbate or relieve the symptoms, what the patient does to improve their symptoms. Don't forget to enquire about the psychosocial aspects in this part and also the hypothesis that the patient has constructed to explain what is happening. Whenever we can we will quantify the patient's suffering (for example, distance the patient is able to walk without discomfort, the number of steps the patient can take without having to stop, etc.). The importance of the symptoms to the patient or the impact on the patient will be established from things that the patient stops doing or does in a limited way: 'what impact does the have pain on your life?’ We will find out which factors may exacerbate or relieve the pain: 'have you noticed anything that makes your pain better? Or worse?’ Finally, ask about the presence or absence of associated symptoms: for example, in the case of epigastric pain: 'what is the pain like after eating?’ Associated symptoms are closely related to each presenting complaint and their differential diagnoses. In general, the positivity or negativity of a symptom associated opens the door of a diagnosis to us (for example, abdominal discomfort which improves in the absence of dairy products may indicate lactose intolerance, or the presence of blood in chronic diarrhoea points to inflammatory bowel disease), hence the importance of knowing the cluster of questions and the exploratory data literally hanging from every symptom or presenting complaint. A good guide can be found at Kraytmann (1983). In any case, we must give ourselves time to open our library of clinical situations and retrieve this information. A good technique for this is the Summary of information obtained.

|

|

Figure 3.1 Use of techniques to obtain specific data |

Summary of information obtained.

This technique increases the reliability, reality and validity of the data obtained. We offer the patient a summary of the data, adding a question at the end: ‘Do you think that this summary is a good reflection of what is happening? Have we forgotten to add anything? Would you remove anything?

The use of this technique has surprising results. The patient feels listened to, but also participates directly in the final picture which forms in our heads. The flow of communication and the quality of data are also reinforced. Note the following example of a patient who believed he had a brain tumour and complained of constant headaches:

I: I'm going to make a summary of the information that I've obtained from your symptoms. Please listen to me carefully and if I say something that is not right, don’t hesitate to correct me. If I have understood things correctly, you have had a headache for three months, located in the front of your head and which is worse in the afternoons. You’ve almost never had discomfort in the morning, although you are having the pain almost daily, is that right? But it seems for three weeks in October, you were almost well and didn’t need to take any painkillers, did you? The three weeks when your headaches were better, coincided with a trip to the countryside. On the other hand, when you have a headache and you take paracetamol this gives little relief, even taking naproxen doesn’t help the pain... am I going in the right direction?

In this case, the interviewer did not include in the summary that these headaches had started after the patient heard that a friend had been diagnosed with a brain tumour, as he didn’t want to prematurely imply that the diagnosis had a psychological aspect. He decided to talk about it in another moment of the relationship. On the other hand, he took good care to confirm that for three weeks the patient had been pain free, as this data along with the absence of morning headaches, makes a diagnosis of intracranial hypertension much less likely (negative predictive value).

Physical examination, if appropriate

Physical examination begins when the patient comes into the room. Listening to the patient is already exploring. Observing also is exploring. Far from dividing the exploratory part of the interview into history taking and physical examination, we assume that they are two facets of the same argument. In addition, physical examination is part of the interpersonal relationship. What can we say about a pair of hands that do not know how to approach a painful abdomen? This undoubtedly discredits all the academic qualifications which may hang on the wall of the consulting room. Physical examination has also a deep symbolic meaning. It's about getting to know another reality, the patient’s reality and to some extent, all about their privacy. There's a common patient reaction when the clinician doesn't perform a physical examination. They usually say something like: «He didn’t even look at me». There's the possibility that the clinician has formed an adequate idea of the problem after half an hour of thorough focused history taking, but from the patient's point of view the clinician hasn't even bothered to “look at me” since there hasn't been any physical contact. The opposite happens when the patient comments: “he has examined me properly”. Physical examination in this context always means exploration. A psychiatrist, for example, is never going to examine in the same manner, not even when their psychopathological exploration has been spotless. Questions can often overwhelm the patient, but examination pacifies them. “A specialist did the same thing as you’ve just done”, could be the kind of comment a happy patient makes to their GP. One of the great things of the clinical act above all is this recognition of physicality, identifying with the other person (and to some extent, putting ourselves in other person's shoes).

We understand by basic physical examination the group of techniques that has a maximal yield for detecting prevalent diseases in each age group and sex. This group of techniques makes us used to the patient's body, its characteristics and what the patient's understands as normal or abnormal. On the other hand, a problem based physical examination (PBPE) (Borrell F, 2002, a, b) consists of a selection of different manoeuvres, orientated around the symptoms whose purpose is to guide us to the cause of the symptoms. For example: ' This patient has pins and needles in both hands, so I must rule out the possibility of carpal tunnel syndrome with Phalen’s and Tinel’s tests.

The best performance of a physical examination occurs when the basic physical examination is combined with the problem based physical examination. On the other hand, it is a mistake to think that history taking goes first and then the physical examination. In reality, as we examine the patient some hypothesis may occur to us and to corroborate them, we combine questions with examination manoeuvres. This is what we call history taking integrated in the physical examination.

Practical example: a 'broken' patientAbbreviations: D: doctor; P: patient |

|

|

TASK |

DIALOGUE |

|

Reading the most important data and planning the objectives |

Doctor reviews the patient's medical records. He sets his own goals: 'it's been long time since this patient last attended and he hasn’t had the minimum health promotion done, this must be done'. |

|

Cordial greeting |

D (shaking hands): How are you Mr Saunders? |

|

The patient defines the presenting complaint |

P: Fine thanks, I come as I am concerned about something... I'm afraid I have broken something, I am 'broken'. |

|

Preventing additional demands |

D: I will examine you shortly but, is there anything else you would to ask me about? P: No, no D: Tell me more about this pain. |

|

Active listening, vanishing point |

P: I was carrying a heavy weight and I felt a severe pain in my groin. D: When did this happen? P: A month ago |

|

Makes a focused history of the groin discomfort, but when some discordant data appears, he also integrates it into the focused history. |

D: Since then, how have you been feeling? P: Fine, but I am constipated. D: Do you feel a lump or do you have pain in the groin? P: No I don’t have a lump or pain, but I feel very constipated and someone told me that this is a symptom of an obstructed hernia. |

|

Ascertains and completes data |

D: Did you open your bowels every day before? P: Yes, I think so... D: Do you remember having any previous episodes of constipation like this one? P: No, I don't. D: How long have you been constipated? P: Around three weeks...

|

|

Summary |

D: Let's see... if I've understood this correctly, you think you are 'broken' because you felt a pain when you lifted a heavy weight, but you don't have any discomfort in the groin. You are concerned about your constipation. P: Yes, this is. |

|

Ascertains and completes data |

D: Have you lost any weight? P: No, no. But during the night, I have to get up and go to the fridge. I eat anything I have in front of me. |

|

Tries to jump to the psychosocial aspect |

D: Do you feel hungry or do you feel anxious? P: I feel anxious, worried, I don't know... well... my daughter has left home, things happen. |

|

Suggested addition with signalling value |

D: But you cannot stop worrying. |

|

The patient returns to their physical symptoms and the clinician respects this 'resistance' to talk about the psychological aspects |

Yes, I think this makes me more constipated. I open my bowels once or twice a week now, but I used to open my bowels every day. |

|

Activates focused history, concentrating on the constipation again |

D: Do you have hard stools? P: Yes, sometimes when I open my bowels I can see blood in my stool...but I have haemorrhoids. D: What is the blood like? P: The colour?...It is red, bright red and around the stools. This has been happening this week, but it has never happened before. D: have you tried a laxative or anything like that? P: No, my wife says I could try an onion enema, what do you think? |

|

Attempt a psychosocial jump again, being very careful not to force the patient’s resistance. |

D: Well, we can talk about this later. Now I would like to know how your mood is. P: I am always very positive, but after everything that has happened at home... it is very hard... so I would rather not talk about it. |

|

A bridging sentence to accommodate the physical examination. You have planned an examination, but during the examination some new areas from the history taking will be opened depending on the findings. |

D: Of course. Let's move to the examination couch and check if you are 'broken'. We could also do a general examination, if that is ok?

|

Observe the set of these techniques in the practical example 'a broken patient'. The first few minutes of the interview has revealed quite a lot of data and quite complex has material come up. Has the focused history been adequate? We can apply the clinical report technique, we can try to synthesise the data we have found: 'a patient without any significant past medical history and with some health promotion data needing completion, comes to the clinic as he thinks he has an inguinal hernia after lifting something heavy a month ago. He has been constipated for the last 3 weeks without any previous history of constipation. He has rectal bleeding in the form of fresh blood around his stools. He thinks both processes are related'. At this point we can see that the chronological characterisation of the blood in the stools has not been sufficiently completed. Missing questions such as: has this happened previously? Is this only recent, as the story seems to infer? Finally, the clinical can plan a problem based physical examination, for example: 'a basic examination needs to be done to this patient to complete the basic data, a superficial and deep examination of his abdomen needs to be performed, including a specific examination to detect an inguinal hernia and I must do a rectal examination looking for blood, anal fissures or haemorrhoids (mostly internal) and tumours'. It is important that each manoeuvre has intentionality: 'in the rectal exam I will look for anal fissures, internal haemorrhoids and tumours'. A hunter does not catch anything if he is not careful, if he cannot imagine the type of movement the brush makes that suggests there is hidden prey. Something similar happens with the physical examination: we are hunting for abnormalities, but to find them we must evoke the image of what we are looking for, even before performing the manoeuvre.

Mistakes to avoid

We summarise in Table 3.3 the main errors that should be avoided, errors that are discussed below.

|

Table 3.3. Technical mistakes in the exploratory part |

|

Intuitive interviewers and field dependence. Focalised interviewers Blocking patients and interviewers who ask a lot, but... by using closed questions Skimming too quickly over the psychological aspects |

Intuitive interviewers and field dependence

Please read these definitions carefully: The intuitive interviewer has a tendency to make up data which actually has not been proven sufficiently. The field dependent interviewer: his attention floats over materials that come out in conversation, without following an interview plan. Unfortunately, both syndromes can often co-exist in the same person, giving a typical pattern of dispersed interviewer. For example:

P: The itching in my legs doesn't allow me to sleep. I did what you told me and used the glycerine soap I also wash my clothes with this soap, but it has made no difference at all...

I: Does by chance the itching get worse with temperature changes?

P: I think is the bed... I get into the bed and the itching starts... could it be fleas?

I (loses his interview plan and falls into the field dependence): Do you have pets?

P: We had to give away a cat years ago because it gave me asthma.

I (field dependence again): But now you no longer have asthma symptoms, do you?

Respecting the will of the patient is an objection which is often used as a reason not to follow the interview plan. However, our goal is to obtain good data for our brain in order to think better and to be able to make better decisions. There is only one situation when is better to be dependent on the field: when we want our interviewee to feel comfortable, Shea (2002) has named this strategy 'feeding the homeless'. In the sense of wandering around with the patient, in an unhurried manner, seeing the material they select. It is an appropriate strategy to meet a suspicious or defensive patient, if we have an interview plan as a reference.

Focalised interviewers

These are interviewers who contemplate the spectrum of health-disease from a psychosocial perspective or a biological perspective, but have difficulty in integrating the two perspectives. They are unable to take an extended history, that is, history taking that considers not only the package we call focused history taking, but also the other two packages: the psychosocial and the patient-centred packages. We distinguish three types of focalisations:

-

Biological focus: Everything psychological remains in a residual category typed as: 'anxious-depressive', 'functional' or worse still, 'hysterical'. A biologically-focused professional will believe that, first and foremost, the 'organic' cause must be ruled out, and then we will consider the psychological 'by exclusion' of other causes. It is very common that in a patient who complains of 'feeling dizzy' we check their blood pressure, we perform otoscopy, fundoscopy and neurological examination... but nobody asks how their mood is! In table 3.1 we illustrate some questions for what we call the psychosocial jump.

-

Psychological focus: A psychological focus consists of attributing the causes of suffering exclusively to psychosocial factors, and the search is focused on this field. Medical professionals often forget the psychosocial aspects of the illness (Engel GL, 1977; 1980), while nurses have, on occasions, the opposite trend. A dermatological problem can be interpreted as 'poor hygiene', high blood pressure readings or blood sugar levels to 'she is always nervous', etc. While a patient often excuses a professional who confuses their depression with osteoarthritis, it they do not often forgive the opposite mistake. The verb 'balint' has been coined (verb derived from Balint, in allusion to the well-known psychiatrist, Gask L, 1988; Aseguinolaza L, 2000), to refer to the following scenario: 'A complicated patient in whom a concrete disease or a lasting relief weren't found, that after empathic listening, the patient shares a relevant intrapersonal conflict; after sharing this conflict, their symptoms disappear'. Without a doubt, some patients may respond to this scheme, but they are very few. In general, we can say that a purely psychological approach means ignoring relevant organic causes of the disease. Imagine patients with hypothyroidism, with their tiredness, aches and sleep disorder, being subjected to a third degree cross-examination in search of the conflict they have to verbalise to begin to heal. Everyone has some degree of conflict or psychosocial stress, so these kind of connections are plausible if the interviewer perseveres with them, and with impressionable patients you can cause them to refer to sexual abuse that has not happened (so called "false memories of abuse', Ratey JJ, 2002, p. 270).

-

Symptoms focus: it takes only one question such as: 'are you happy with what you are studying?', 'how is your mother feeling?' for the person to come into the consultation instead of the disease. Gross DA (1998) found more satisfaction in interviews where some social interaction was produced. However, despite requiring a minimum of effort, many interviewers prefer to remain in the tangle of symptoms appreciating only exploring things on a superficial level.

So, and as a practical conclusion of the foregoing up to here, how should one proceed to a collection of data that has enough bio-psychosocial 'extension'?:

-

Practice the 'vanishing point' of the interview and the 'emptying of pre-made information'.

-

Be aware of the first hypotheses that occur to you. Practice reframing to doubt this, with the 'reverse hypothesis 'technique': 'I'm considering a hypothesis of a biological nature... and if the problem was in the psychosocial sphere?' Or vice versa.

-

Bring the 'whole person' into the consultation. Although you only need to ask a question concerning interests, hobbies or family... do it!

Blocking patients and interviewers who ask a lot but... by using close questions!

The natural tendency of any interviewer is to use closed questions, i.e. questions that can be answered with a 'yes' or a 'no', and to focus their attention on the aspects of the presenting complaint, which can be solved more easily. This combination leads to induced interrogations: we take the 'clearer' symptoms and we forget the most vague and difficult to work with.

The less effort a patient has to make to answer a question, less reliable the answer. It may also be that the patient answers 'yes' or 'no' to a closed question with the secret hope of pleasing the interviewer. Avoid this trend by including sentences such as: 'tell me more', 'what else happened?', etc in your repertoire of skills.

Skimming too quickly over the psychological aspects

Respect the patient’s psychological defences. Note the aggressive style of the interviewer:

P: I have come about this headache. I think it comes from my neck.

I (making a premature emotional signal): You look worried, even sad.

P: No at all, I feel fine.

I (Again using an emotional signal, followed by an interpretation): I note you close your hand and you frown as if you are experiencing a lot of tension.

In terms of emotions, everything has its own pace. Cautious approaches have advantages:

I (while examining the previous patient): I see your muscles are very tense...

P: I’m always told this, but I'm fine.

I (suggested interpretation): Sometimes stress, or everyday problems, show themselves in our backs...

P: I don’t think so. I have this headache and it is not related to stress.

I (giving in): of course, your headache. Let's take your blood pressure...

Although we have a strong suspicion that there are psychosocial elements influencing the patient's symptoms, we will have to delay addressing them until the patient opens the door slightly.

Situations Gallery

In this section we will examine:

-

The vague patient.

-

Difficulties getting into the psychosocial aspects.

-

Starting from scratch!

-

Pelvic examination.

-

History taking of sexual behaviour and risk assessment.

The vague patient

Assume that the doctor has already introduced himself and properly greeted the patient when this scene begins.

Abbreviations: D: doctor; P: patient.

/1/P: Doctor, I wake up very often during the night to pass urine.

/2/D: Do you have a burning sensation when you pass urine?

/3/P: No, what happens is that I get nervous and I have to get up.

/4/D: And why are you nervous?

/5/P: I don't have any reason to be nervous... I think I wake up because I feel some nerves in my legs and if I don't get up... I explode

/6/D: So, you come today because you don't sleep well at night, do you?

/7/P: No, I come today because I have to go to get up at night very often to pass urine.

/8/D: And then do you pass a lot of urine?

/9/P: Sometimes only a little bit, that is why I am surprised.

/10/D: And sometimes you don’t even pass urine?

/11/P: Yes, I do.

/12/D (irritated): So what a mess, there is no clarification.

Comments

1. Has the doctor any reason to complain about this patient who is seemingly confused in their responses?

Doctors have an idealised image of how a good patient should be. We would like the patient to understand our haste and collaborate by providing reliable and ordered data. When the opposite happens, we cannot avoid feelings of irritability, and we easily think: 'this patient is so annoying' rather than think: 'the data I need to get a good diagnosis is here, but it depends on my ability to know how to get it. Patients do not have any obligation to be the good patients that practitioners want, and instead this idea of a good patient harms the interviewer who holds it. The right question is not: 'why isn’t this patient a good patient?', but: 'what should I do to accommodate this patient?’

2. Does the doctor make any mistakes? If so, which ones?

The interviewer still corresponds to a field-dependent style. As previously described: field dependent interviewers set the questions and the interview plan in general, from data provided by the patient at each point of the interview without generating the necessary hypotheses to 'detach from' the symptomatic field and to create a proper interview plan.

3. Does the Doctor’s clarification of the presenting complaint in /6 /seem correct to you?

/6/D: So, you come today because you don't sleep well at night, do you?

Clarifications always help though, as in this case, they are not formed in a particularly skilled manner. They help because they force the clinician and patient to agree on the material they are going to work with together.

It is preferable to obtain a 'no' or a rectification from the patient to an inaccurate clarification, than a forced agreement.

4. Could you think of any possible diagnosis which could justify this patient's presenting complaint?

If the doctor applied the textual listening technique (read what they have just heard as if it were written and belonged to an anonymous patient), he would obtain the following semiological data:

-

This is a 55 year old lady who has to get up at night to urinate.

-

She describes feeling a sensation of 'nerves in the legs' which force her to get up, and if she doesn't do this she 'explodes'

-

There aren’t any clear urinary symptoms being described.

If the doctor 'had read' this data, as now you do, instead of 'having heard' it in a slightly confused context, he would certainly consider the following possibilities:

-

Restless legs syndrome in a person who additionally suffers from urinary frequency of another origin.

-

An initial presentation of heart failure with a degree of nocturnal paroxysmal dyspnoea, which the patient confuses with restlessness

-

Anxiety which the patient somatises as an urgency to urinate.

We mention these possibilities, but undoubtedly there are more. What interests us here is the blockade to the patient’s story permitted by the clinician, and their anger at the patient's seemingly confused style. This irritation leads the clinician to trivialise the patient’s symptoms (‘these complaints are nonsense').

What must we do in such situations?

1. There cannot be a good interview without defining the presenting complaint well. Direct the interview towards achieving this, even if you have to interrupt a very talkative patient. The patient will accept the interruption and restarting the interview if the clinician does not show signs of nervousness or irritation. More specifically, the doctor will be able to 'draw' a map of complaints, which is, to explore all presenting complaints from the patient without ranking them, and to allow the patient to suggest to you the reason for consultation. For example:

/4/D: Ok, and is there anything else worrying you?

Opening the map of complaints allows the doctor to use it as a symptom-guide to choose the one that appears to be the most relevant.

2. Let it be the patient be who chooses the importance of their symptoms. Sometimes it can be useful to say: 'Of all the things which you have told me about today, which has brought you in today?', or even, when the patient raises some difficult personal problems to solve we can try: 'what do you think I can do to help you?'

3. Clarify: 'what do you understand about...?' Another similar technique is the forced clarification: 'please, could you try to explain your dizziness without using the word dizziness?’

4. A very useful technique is creating scenarios: 'How would you feel if you had to stand up?', 'What would happen if you had to walk a hill?' 'Let's imagine you find the shopping trolley and had to go up to the top floor', etc.

5. Menu of suggestions: the discomfort you feel... is it a sharp pain or a feeling of pressure?

6. When a patient expresses their self in very unclear way, or you have the feeling of 'being completely lost', consider the possibility of starting from scratch (as if you didn't know the patient) and apply the 'map of demands and complaints', 'pathobiography' and 'textual reading' techniques. In this situation, relax, take your time and let your mind work freely. Do not force yourself to 'demonstrate' that ' you were right', but quite the opposite: 'and what if I was going down the wrong path until now?' (This technique is named the 'reverse hypothesis technique'). Try to be a good listener to the echoes which the patient's words evoke in your head. How many times do clinicians recognize in hindsight that, at some point, we considered the correct diagnosis, but discarded it because we considered it to be 'unlikely'!

7. In elderly patients and patients who are cognitively impaired, the help of a family member or a carer may be essential to enable the clinician to understand exactly what happens, what are their daily activities, whether they take their medication or not. This should be a team task. Sometimes our principal task consists of mobilising family resources so the patient is cared for in their family environment.

We’re going to implement some of these ideas in the example above. Interestingly, the case is very easy to solve simply with the ‘repetition of words or phrases’ technique, which allows us to clarify the content of what the patient said:

/1/P: Doctor, I wake up at night very often to urinate.

/2/D: I see... Tell me more about that

/3/P: I get nervous and I have to get up.

/4/D: Are you nervous?

/5/P: I don’t have any reason to be nervous. What happens is that I wake up because I feel some nerves in my legs and if I don't get up... I explode

/6/D: I understand...if you don't wake up, you feel you would explode?

/7/P: The feeling I have in my legs means I can’t hold them still. Touching the cold floor is the only thing which relieves the feeling.

At this point is becoming quite clear that the patient describes restless legs syndrome, and that the confusion came from the relationship established with urination.

Also note these skills in another fragment:

/1/P: I feel dizzy; this tiredness is actually getting worse. I get up from the chair and I feel dizzy, I have palpitations and I feel short of breath too. I feel scared even walking into the corridor, as I know all my symptoms will get worse.

/2/I (clarifying): What do you mean by dizziness?

/3/P: When I wake up in the morning and when I get up from the chair, I start feeling the dizziness again.

/4/I (forced clarification): Try to explain the feelings you have when getting out of bed without using the word dizziness. (Creating a scenario) You get up from your bed and...

/5/P: Well, I get up and I lose my sight and then I feel sick! I say to myself, 'calm down, and don’t move your head' and then I seem to recover a bit.

/6/I: Can you reach the toilet without help?

/7/P: Yes, but holding onto the walls and walking little by little

/8/I (menu of suggestions): Do you feel weak or do things spin around you?

/9/P: As if I am losing sight of the world. Really really bad dizziness

In just a few minutes of interview we have achieved relevant information about the patient’s symptoms, which guides us towards positional dizziness. However, several symptoms have appeared and we follow them: a) breathlessness on exertion; b) an increasing dizziness when the patient leaves the room. The initial data points towards heart or respiratory failure, the second part points towards symptoms of anxiety. We must follow each one of these possibilities.

|

In summary, in front of a vague patient:

|

Difficulties getting into the psychosocial aspects

We have previously referred to two types of very common difficulties in the exploratory part of the interview: a) drawing the chronology of the symptoms sufficiently, and b) addressing the psychosocial aspects. These difficulties are reflected in the following example:

Dr.: How can I help you today?

P: A get a very severe dizziness from time to time. I think I may have something in my ears.

Dr.: Is there anything else?

P: No, just this. But when I get feel dizzy, it is very strong, I almost fall over, I have to support myself, and then it disappears. I get very scared.

Dr.: Have you noticed any hearing loss?

P: No, no.

Dr.: And double vision? Or headaches?

P: No, nothing like that...

Dr.: Have you had any ringing in your ears?

P: No.

Dr.: Ok, do you mind getting on the couch? I would like to examine you.

Comments

1. Have characteristics of the symptoms been sufficiently established?

The interviewer ignores important aspects such as: when and how the symptoms started, what exactly the patient means by a sensation of dizziness, what has happened to the symptoms over time, what makes the dizziness worse or better, what the patient relates the symptoms to and what their beliefs and expectations are about these. Strangely, this type of short history taking is performed by professionals who have many years of clinical practice. It is as if by knowing the presenting complaint and the patient's appearance, they already knew what happens to the patient (intuitive interviewer).

2. When can we be sure that we have made taken a sufficient history?

We talked previously about the 'medical report technique'. It consists of asking yourself: 'with the data I have, could I make a clinical report about what is happening to this patient?' Try to document in the medical records a report which includes the how, when and where of the patient’s symptoms and you will immediately detect your gaps.

3. Is it important to address the psychosocial aspects?

It is very important. In a large proportion of patients suffering from dizziness, their symptoms are due to psychosocial processes such as: anxiety, depression, adaptive disorders, etc. The patient's hypothesis of, 'I think I have something in my ears', can make it difficult for the clinician to explore the psychosocial aspects. In any case, we must learn to distinguish the symptoms which could be due to an underlying psychosocial cause, and not hesitate to make the psychosocial leap.

4. How can we get into the psychosocial aspects without raising psychological resistance?

Some patients react badly when they are asked: 'Are you somewhat more anxious?', and especially if they are told directly: 'All this is anxiety'. Questions related to the 'psycho-social package' might be more acceptable to the patient if we start by saying something like: 'How do you rest at night? Or: 'how is your mood?' Although we do this, we could precipitate resistance like in the case we will analyse next.

What must we do in such situations?

Let's look at the example above, but selecting the moment when the professional makes the psychosocial leap:

Dr. (summarising): if I understood correctly, you feel sudden dizziness, lasting just a few seconds, as if you are going to lose your balance. It happens anywhere and it has been going on for 2 months. Is this correct?

P: Yes, it is.

Dr. (psychosocial leap): Has your sleep become worse?

P: Yes, it has.

Dr. (After finding more details about the patient’s insomnia, they continue by saying) how is your mood at the moment?

P: No, this is not related to stress, because I feel fine and not anxious.

Dr. (facing psychological resistance to explore the 'mind'): I am not saying this is anxiety, but mood is one more aspect of humans, the desire to do things, hopes you may have right now... All those things also interest me. What about that?

P: I don't have many hopes right now.

Dr. (making an emotional signalling): You are saying this as if you were sad...

P (tearful): As you would expect me to be since my wife has left me after 15 years of marriage!

Resistance to tackling the psychological aspects doesn't mean a prohibition. In fact, patients showing more resistance tend to be those who need this type of approach the most. It is a painful step which must be handed with tact and an appropriate technique and skill.

|

Remember, to do the psycho-social leap:

|

Starting from scratch!

Knowing patients for years undoubtedly has advantages, but it also leads to pathology of familiarity. First of all, seeing a patient regularly doesn't mean that we know them. It may well happen that all or almost all of the previous encounters were carried out on a superficial level, without a preventive assessment or a systems review. Secondly, we experience a false sense of security, as if by the fact of the patient having visited many times we have averted the worst case scenarios. This false security is increased with hypochondriacal patients in whom we have repeatedly excluded cancer. There comes a time in which this aphorism is true: 'you come to see me so much that I disregard you'. Thirdly, we process a lot of information provided by the patient as being 'already known' and do not consider it. We divide the profile of complaints into those 'already addressed in the past', and we selectively attend to the 'new' complaints. It is a good strategy if we are scrupulous and write down the exact profile of presenting complaints. There is a difference between the patient who presents with a loss of appetite, and only that, and the patient who is additionally losing weight. In fact, we must periodically reprocess the symptoms which may change in severity or intensity. Remember that a picture of diffuse body pain can precede the onset of cancer (McBeth J, 2003).

Observe the following situation:

P: I can't continue like this! Please take away this excruciating pain or refer me somewhere...

I: I don't understand, what pain are you talking about?

P: Pain in my whole body, you cannot imagine how much it hurts.

I: (Reviewing his medical records): Let's see, I can see previous visits about your high blood pressure, diabetes and knee arthritis, but you have never complained of pain in your whole body before.

P: I mentioned it on previous occasions and you ignored me.

I: It is hard for me to have ignored a complaint which you have only told me about for the first time today, don't you think?

Comments:

1. Which is the best strategy in this type of interview?

The best is to start as if we are seeing the patient for the first time, with the idea of forgetting what we know, any prejudice, and any feelings of irritation towards the patient. 'Not knowing always bothers us, but not knowing in the context of a patient who has come to see us in regularly in recent weeks, tends to irritate us. Starting from scratch is an exercise in true humility!

2. What does 'starting from scratch' really mean?

It means reviewing patient's medical records, verifying and completing generic data, particularly the family and psychological history, and start taking a new history at least on the current complaints. The pathobiography technique we saw in Chapter 2 can be of great help.

What must we do in such situations?

In the following situation the patient came seven days ago with acute bronchitis that has improved. Today he comes for review of his sick note.

I: How do you feel Mr Wright?

P: Bad. I feel very weak. I think that this time the bronchitis is very bad because I have to drag myself out of bed.

After physical examination:

I: I can see that your bronchitis has improved a lot.

P: But I don't feel hungry and I am always sick. I am losing weight. I am not ready to go back to work.

I: Ok, I will do a sick note for another week for you to recover.

Seven days after the following conversation occurs:

I: How are you feeling Mr Wright? Have you recovered now?

P: No, not at all. You didn’t listen to me, and I've already told you that I feel very bad.

I: Do you have a cough or are you bringing up any phlegm...?

P: No, it’s not the cough which making me weak and is stopping me working. I am not working and am weak because I have lost 10 kilos in a week.

I: Ten kilos in a week? This is ridiculous, it is completely impossible...

P: Look at how loose my trousers are to see if it is impossible...

At this point the interviewer literally does not know where to start, so he decides to start from scratch. After reviewing the patient’s family and past medical history, he addresses his current disease again, but from a new perspective.

I: (Implementing the technique of visualisation chronology-plot-impact): Let's see, Mr. Wright, I would like to start from the beginning as if I’m seeing you for the first time. When did you start feeling unwell?

P: In fact, for the last month I have felt my digestion is slow... Yes, I have not been eating well or feeling well after eating for a month.

I: And then you had bronchitis.

P: That's right, but I would say that I was already feeling weak... could it be that my defences are low?

I (Ignoring the patient's questions and performing a summary): Allow me to continue: if I have understood correctly, you have lost your appetite and some weight over the last month... is that correct?

P: I guess so. When I came with bronchitis, I asked for some blood tests and a chest x-ray, but you said it was not worth doing.

I (Ignoring the accusation): Indeed, about 15 days ago you started coughing, having a fever and feeling more fatigued, is this right?... And when you recovered from the cough, you’ve still lost your appetite, and food, you say is disgusting...

P: Exactly, I can't eat anything. I've been eating soups and juices for the last 10 days... could this be due to the antibiotics I was taking? But this was also happening before I took them.

The interviewer continues with his task to establish that the patient has been off colour for a month on which a self-limiting acute bronchitis is added. Later investigations show the patient has stomach cancer which is beginning to invade the portal space. If the doctor had been stubborn in his first hypothesis ('this patient only wants to lengthen his sick note'), he would have delayed the diagnosis with consequent blame from the patient: « you have 'you told me I had bronchitis and actually I had cancer'.

|

Remember, in the face of an unclear clinical picture:

|

Pelvic examination

In a culture of modesty, the pelvic examination is sometimes delayed to avoid making the patient feel uncomfortable. This is a big mistake. We should normalise this type of examination: 'we routinely do rectal examinations on people of your age', 'this examination is quick and is at least as important as an X-ray', etc. Observe how this practice nurse introduces a pelvic examination:

N: We will now proceed to a pelvic exam. In your case I will need to make a pelvic examination with my fingers first to see if there is a problem with your womb. Sometimes a problem occurs in this part and we need to do a therapeutic curettage

P: I had a scraping when I had an abortion.

N: Then you know what I am talking about. Anyway, as you are not asleep now, after doing a pelvic examination with my fingers, I will introduce the speculum gently, and I will open it to see the cervix... you have had this done before, haven't you?

P: Yes, for a smear test.

N: I see, so you know it is not painful and it allows us to rule out any cancer or infection and to take a sample and analyse it in order to further check there is not a problem. Actually, I think that the problem may be in your womb, but while we are examining you, we can do a smear test.

Comments

1 Do you think there are any mistakes or aspects of the interview which could be improved? In general, the interviewer was very correct, but we could object to her saying:

'Sometimes a problem occurs in this part and we need to do a therapeutic curettage'. At this point she is suggesting hypothetical events.

'So you know it is not painful and it allows us to rule out any cancer or infection'. The word cancer has a high emotional content and it should be avoided. The patient may well think: 'I am having this test as they suspect I have cancer'.

And later: 'I think that the problem may be in your womb, but while we are examining you, we can do a smear test'.

It is inappropriate to give uncertain information (there is still no diagnosis and when we have a diagnosis, this should be given by the doctor), but it is also inappropriate when she says 'while we are examining you', as it implies we are carrying out a somewhat secondary test.

How should we act in such situations?

With assertion. If you do not give importance to modesty, the patient won’t either. For example:

I (Rationality of the examination): We need to do a rectal examination to examine your prostate... (Establishing bidirectionality) Do you know what this examination involves?

P: No, I have never had it before. But my father suffers from prostate cancer.

I (converts the fear into preventive action): This is all the more reason to assess your prostate. The examination consists of feeling the prostate by inserting a finger into the anus... is not painful provided that you are relaxed... Please move to the couch and we will prepare you...

Let's imagine that at this point the patient exhibits resistance and we consider this examination absolutely necessary:

P: I would rather not to do this.

I: (Finding out the patient's beliefs): Why is that? Is it fear, embarrassment or would you like to go to the bathroom first?

P: A bit of everything....

The patient has not organized their thoughts. At this time we can opt to work through them a little bit more, applying motivational interviewing strategies, and even delay the examination by booking another appointment. But imagine that it is a test that we cannot postpone:

I: In your case this test should not be postponed. (Normalises it) This test is something we do very frequently. (Legitimises it) It is normal to feel embarrassed, but think that for us it is something we are used to doing. (Favouring the patient’s control over the situation) If you would like to go to the toilet and come back in a few minutes it is not a problem, but I recommend that you do it now, although you don’t feel prepared. These things are often better if you don’t think about them too much, don't you agree?

Avoid saying: 'if you prefer to come back another day, there is no rush...' as the patient may not come back. Do not mind being a bit insistent, because although the patient can consider you 'annoying' at the time, the prevailing thought will eventually be 'luckily I had the test done'.

|

Remember, overcoming the culture of modesty means:

|

Taking a history of sexual behaviour and risk assessment

To finish this situations gallery, we have chosen taking a sexual behaviour and risk assessment because of its importance. The techniques that we will see are similar to the ones we have to use to take a history of other behaviours (diet history, social history, etc.), with the exception that we are entering an area where we will have to build up the patient's trust. Note the following interview with a 24-year-old man:

I: Before proceeding to address your cold, I would be like to speak to you a bit about risk behaviour. Are you gay or straight?

P: I don't understand...

I: Do you have sex with men or women?

P (Laughing): Mostly with the TV.

I: Do you masturbate?

P: Whenever I am watching Heidi TV series..

I (Confused): Well, I suppose you must have porn videos and such ... right?

The patient does not respond, looking at the interviewer with a mocking smile. The interviewer changes the subject.

Comments

1. What was the error made by this interviewer?

The interviewer introduces the subject abruptly, which makes the patient defensive. He may have become annoyed by being suddenly asked about his sexual orientation and he has retaliated by mocking the interviewer. At this point the clinician doesn't know how to continue and changes the topic.

2. How can we introduce the topic of sexuality without causing tension? Some patients tolerate, and even like being asked directly, but in general it is preferable to use a graded approach. For example:

-

Do you have a boyfriend/girlfriend, friend or partner?

-

How is your intimate relationship with your partner?

-

Sometimes chronic illnesses can cause sexual difficulties, have you noticed any problems?

-

Have you noticed any changes in your libido?

-

Many people today day are concerned about getting HIV; do you have any concerns about this or any risk of infection? (After the patient's answer the interviewer clarifies): As well as contracting it from a sexual relationship between a man and a woman by having intercourse without a condom, receiving a blood transfusion, sharing needles, and men, who have sexual relationships with men, are the most important risk factors... are you in any of these groups?

What must we do in such situations?

We must always try to earn the patient's trust with a gradual introduction to the subject, standardizing our questioning and moving from general questions on the subject to specific questions. In the following case, we are speaking to a 56-year-old woman. We suspect that there is a possible sexual problem that may be influencing her long-standing dysthymia.

I: (Making a summary of the information obtained so far): I can see that your difficulties haven’t changed from what you told me three months ago. However, I would like to move a little further forward today. Something that we have never addressed is whether you are satisfied with your relationship with your husband.

P: Well, once I told you that my husband keeps things to himself. He does not communicate. He watches TV, he reads things related to football, but he talks... little and badly.

I (Screening for domestic violence): have you ever felt threatened?

P: No, never. I don't know how to say this, he isn’t a very affectionate person, but he has never been violent to me.

I (Suggested interpretation): If I clarify, your complaint would be rather a lack of affection...

P: Yes, it is.

I: And on a more personal level, is there an intimate relationship?

P: No, because he is unable to talk about serious topics.

I (He realises that the patient hasn't understood, so he clarifies the question): I mean what is your sexual relationship with your partner like...

P: For at least three years he hasn't asked me anything. Sometimes I tell him 'we are very young to be celibate, why don't you go to the doctor?' But he doesn't want to discuss it. He says that his hernia prevents it. You tell me...

Don't forget the golden rule: For sexual and risk behaviours we always need to be very clear. We can start the dialogue in a metaphorical way, but if we have to ask a second time we must make our communication as clear as possible.

|

Remember, for risk behaviours:

|

Advanced Concepts

Generally, the different phases of the interview analysed up to here take a very short amount of time. We greet the patient, we find out the presenting complaint, and in less than a minute we proceed to the verbal exploration. In the initial moments of the interview, the interviewer will have proceeded to obtain the readymade information, and apply techniques of narrative support. From the initial information; the interviewer will have generated their first hypothesis trying to answer two important questions: 'What is happening to the patient?', and 'what am I expected to do?’ This is the framing or the interview's intention. The interviewer will start making assumptions in an automatic way (hypothesis generating), and from them they will produce an interview plan (Burack RC, 1983; Esposito V, 1983; Boucher FG, 1980). In the following pages we will see the necessity of combining these hypotheses and thoughts (advanced interview plan) with a basic interview plan. Following this and using the data we have obtained, we need to apply a process to decide which hypothesis to keep. This is a highly complex process where we combine two types of thought: intuitive thought (or thought guided by analogies and similarities) and thought guided by criteria. Finally, we will examine the bio-psycho-social model and what it brings to the diagnostic task.

Drawings in the mind

One of the most important challenges we face in the clinical interview is whether different clinicians obtain a similar diagnosis in the same patient and clinical situation. Studies on the subject are named diagnostic variability studies and they cover the fields of both medicine and nursing. We have the impression that one of the key elements which explains the differences between clinicians when analysing their patients' problems is the way in which they learn, or expressed another way, by the images in their mind of the different problems or clinical situations. Let's briefly examine this point and we will also give some pointers on how we can share these mental drawings more efficiently, which is so important when interpreting the clinical reality.

First statement: when we try to understand a clinical situation, we don't use an intuitive method. It is not true that we collect data and a diagnosis or a way of describing the problem just appears in front of us. We always have a few previous schemes or models, which we use to interpret the reality of the situation. Knowledge, as Popper understands, is always reasoned (Popper K, 1972). Due to this, for many years doctors have been applying all kinds of diagnoses to patients with fibromyalgia, and we now probably see patients who in the future we will group under different headings. We only see what we are prepared to see. We only see what we somehow already have in our brain as a model.