Resumen

Índice

- Key Ideas

- Basic skills for listening

- Establishing a relationship: the impression the Doctor forms of the patient.

- Exploring part of the consultation: the semi-structured interview

- Importance of the first minute

- Delineating the presenting complaint. Map of demands and complaints. Pathobiography

- Exploring beyond the apparent presenting complaint

- Active listening 'the interview leak point' and the technique of 'pulling the thread”

- Textual reading and suggested addition techniques

- Framing and reframing the interview. Resistances.

- Mistakes to avoid

- Attitudinal errors

- Technical errors

- Situations gallery

- When listening hurts

- The patient with multiple complaints

- The intruding relative

- When the doctor and patient speak different languages

- Advanced concepts

- Types and purposes of listening

- Listening and emotions

- Good communication versus poor communication

- Therapeutic commitment

- The good listener

- The importance of non-verbal communication

- Time management

- Summary

- Bibliography

Listening to the patient

Key Ideas

-

Listening is predicting what will be said and being surprised when it does not match.

-

Only the curious listen well, others become bored ... and switch off!

-

Those who ask get answers, but only answers (Balint M, 1961).

-

Those who allow the patient to talk get stories.

-

In the first minutes of the interview, especially, if we let the patient talk, we may extract rough diamonds which may not re-emerge.

-

There is no possibility for empathy without developing patience.

-

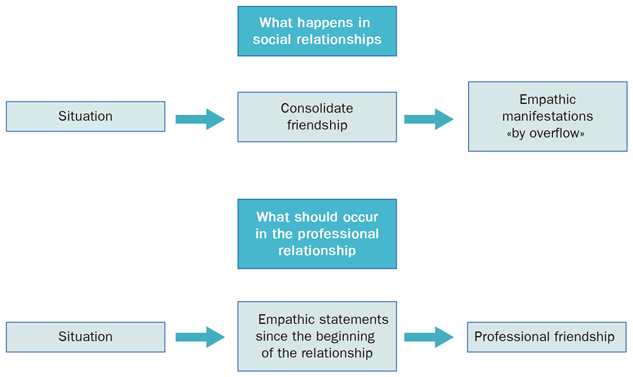

Empathy, in contrast to the sympathy of friendships, maintains an emotional distance from the patient's suffering to enable better and fairer decisions.

-

Those who don’t know their areas of irritability are at the mercy of their negative emotions.

-

Hidden hostility and resentment in the doctor-patient relationship puts the doctor at risk of clinical errors.

-

Knowing a person is to discover the stereotype that we were applying and to dispel it!

-

Working out our “perplexity point” is to recognise that 'we don't know' what happens to the patient, and resist the temptation to deny this or conceal it with 'routine' solutions and to be aware we may need to look beyond the apparent presenting complaint.

Basic skills for listening

Our lives are the years we have lived, our experiences which have made us who we are, and the fortuity to have been born and be alive today rather than someone else. We have the task to understand others and to make ourselves understood, because to communicate is to share, but in doing so is to take a risk. Just sharing who we are is taking a risk.

What does one know about another person? Firstly, starting to know something about someone else is to question the information already known or which is thought to be known from to third parties and process the information for ourselves. Be open to surprise. The other person is a draft which needs to be confirmed in each visit, they are not a static picture. Knowing something about the patient also requires us to relearn our profession, because unlike a bank account, our knowledge doesn’t produce revenue. In a few years, if not months, the lazy clinician becomes an expert in prejudice. The idle person considers the patient from their own convenience, either trivialising their complaints or dogmatising what needs to be done or not done, in an attempt to remove the complexity of the situation and save themselves the effort of rethinking things. Because our expertise is not innate, it is always created from our current experiences, in the most recent months of our lives. Our continued expertise is built as a result of our continued will to excel in our field and, due to our desire to be the best of ourselves. Only those who reflect, or at least try to reflect on each clinical situation experienced, is a skilled and responsible professional because such reflection is a key principal of continued professional expertise. When we inevitably make a mistake, because we are human, the moral pain experienced, is mitigated by our deep conviction that we have properly considered the decisions taken.

On the other side, we have the professional who falters. The first phase is barely perceptible, and undoubtedly the most dangerous. Whatever happens is not that one suddenly thinks: 'today I stop being a good professional'. Of course not. The first imperceptible step is the step toward mediocrity. Mediocrity does not consist of doing things wrong, but of not wanting to do things better. The professional who slides into mediocrity says to himself... 'only today' I will let myself do my clinic a bit worse 'only today' I will not strive to listen, 'only today' I will dismiss the suffering of patients by responding with platitudes, 'just today'... But the 'only today' becomes routine. When laziness overcomes us it does not comply with only today, it always wants tomorrow. Then patients begin to wonder (and even to say), 'you are no longer the same as before'. When the professional accepts this, they accept nothing less than the loss of their self-esteem and from here slides inexorably into despair. If a hint of pride is left, it will motivate them to either seek other sources of intellectual compensation out of work, or they will divide their activity into 'routine' and 'research', in search of the area where they can say: 'Look what I am capable of doing, please, don't take everything else into account'. But 'everything else' tends to be what matters most to patients. Everything else, really... is what counts.

That is why the professional who has been in clinical practice for many years is united with the one who has just begun: both should look to the patient and the doctor-patient relationship with the fresh eyes of the beginner. As León Felipe tells us:

«That the things in the soul and the body do not scar so we never pray as the priest prays nor as the old comic says the verses. Not knowing the role, we will do them with respect...»

To these marvellous verses, Xavier Rubert de Ventós adds: we must overcome the inertia of habits (Rubert de Ventos X, 1996). There is a need to recapture the enjoyment of working and give the quality of adventure to everyday life.

This chapter will help us with this task. We will see, first of all, how we get an initial stereotype of the patient and the first frame of the clinical situation and how important is to be attentive to challenge this first stereotype and frame. We will also see some techniques to integrate patient data, mapping their demands and complaints, to allow the patient’s narrative during the first few minutes of the consultation, and to discover their way of making a gesture or a comment without importance. We will also learn to recognise when we are in emotional flow with the patient, what are the attitudes that separate us from this purpose and techniques to facilitate the patient’s narrative, all in a limited time frame.

Establishing a relationship: the impression the Doctor forms of the patient.

We said in Chapter 1 that three capital functions occur in the clinical interview (Cohen-Cole SA, 1991): We establish a relationship, we find out the profile of health and disease, and issue a series of information and tips. Let's see how we form a picture of the patient while listening too.

The image projected by the patient

We are very quick to label people. We do it by stereotyping, i.e. from one (or a few) salient traits, we guess if the person is honest, or the tasks which we could share. We need to do this to anticipate dangers, behaviours and opportunities. Since we were young we have allocated a part of our intelligence exclusively to do so. It is not something we are taught at school or university, but as a result of this intuitive thought our environment seems safer. We move aside from people whose reactions are unpredictable. Whilst simultaneously we strive to make ourselves predictable to others and we try to change our behaviour depending on their reactions.

We can only say ‘we know a person’ when we can more or less accurately predict their conduct. There is no real knowledge without predictive ability, that's what distinguishes mere speculation about a person’s behaviour from well-established knowledge. A technique to become more aware of another person’s character is to contrast the first impressions or quick judgments that form in our mind with what we can later confirm to be the reality. For example: "I think that this patient will be disorganised and will have difficulty taking medication correctly". Some predictions will be confirmed, but others will be refuted. The latter give us an opportunity to learn. Expertise is built on recognition of our mistakes. Here are some tips to guide us:

-

A person who acts decisively does not have to be intelligent or strong willed.

-

A very friendly person is not always a good friend. Warmth is a good business card which both good and bad people have learned to use.

-

A person we dislike can be an exceptional person, with great virtues that we aren’t aware of. And vice versa.

How do we go beyond the topics in this book, in our task of getting to know others? Adolescents are very polar with their perception of people: ‘I like/ I dislike’; they are expressions which do not accept intermediate positions. With age, we learn to be more even-handed and there comes a time in which we understand almost everyone, although there are people that elicit more of our sympathy than others. This natural evolution is positive, because it puts on hold negative stereotypes, and we give an opportunity to the patient to surprise us by contradicting the stereotype. One way to counter negative stereotypes that we form our head is to ask ourselves: ‘what if this person who I dislike, turns out to share something which is important to me or we share the a hobby which I love?’

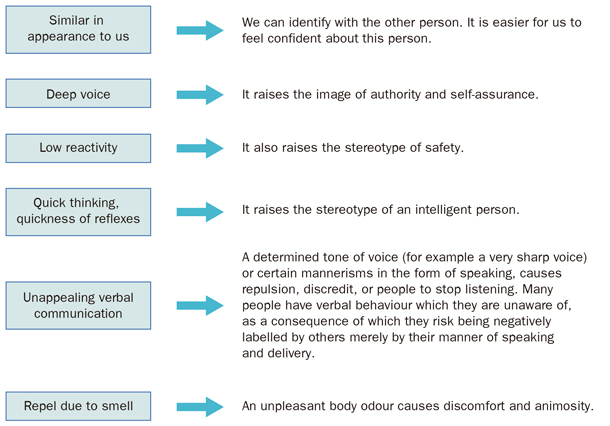

It is worth knowing the following corrections to errors of attribution (Borrell F, 2001 [Figure 2.1]).

In summary is it possible to, know people by stereotypes? Yes of course, it is impossible to break from them. We have a few boxes where we place people. The challenge consists, on the one hand, of counteracting negative stereotypes, the extreme judgments of black and white, and to expand the range of greys, and on the other hand, knowing the boxes which we use to place people in.

|

|

Figure 2.1. Corrections to errors of attribution. |

Exploring part of the consultation: the semi-structured interview

For years we have been defending the view that health professionals should have a habit of work based on well learned tasks. We call this group of tasks a semi-structured interview, we summarise the exploratory part of this below.

-

Review the list of problems or the patient summary.

-

Cordial greeting.

-

Define the presenting complaint. The patient’s demands and map of complaints. Pathobiography.

-

Active listening ('vanishing point' of the interview).

-

Verify and complete data.

-

Summary of the information obtained.

-

Physical examination, if required.

In this chapter, we will address the first four points.

1. Before the patient comes to the room: review the list of problems or the patient’s clinical summary.

One of the great challenges of the clinical interview is to integrate the data we already have from the patient. The ideal would be to read the complete medical history before the patient comes into the room, but this is rarely possible. If this is not possible, the medical problem list, medications, investigations and the last consultation are the parts of the history that help us to become more oriented. We recommend the technique of open summary or open epicrisis (equivalent terms). It consists of a summary that is updated at each visit (especially when there are new additions), and must be readable in just a couple of minutes. It is the place where we explain about the patient: ‘since the patient became widowed, he is sad, his pain has become worse, he doesn’t have good adherence to his medication and his hypertension (HTN) is not well controlled’, which is different information from reading a list of problems such as 'hypertension, depression'. It does not exclude the list of problems, but it complements it which is advantageous. It is important that this summary includes phrases such as: ‘principal problem of this patient is...’, ‘must be controlled periodically...’, ‘in case of such a complication we suggest...’

An aphorism that we coined in the 1980s says: ‘an incomplete history remains incomplete until it reaches a Good Samaritan’ (Borrell F, 1988). Don't miss the opportunity to complete the basic data shown in Table 2.1. For data collection for a complete database, and a review by systems.

A particularly annoying situation is when a patient comes and stares to us. The doctor asks them: ‘how can I help you today?’ to which the patient responds with some displeasure: ‘You know!’ The doctor insists: ‘what do you want to ask me today?’ To which the patient responds, almost angry: ‘You told me to come today to review my blood results’. The case illustrates poor integration of data prior to the consultation.

|

Table 2.1. Database of medical history |

|

Family history and relationships. Job and hobbies. Past medical history, previous surgical interventions, drug history. Smoking habit, alcohol intake, use of recreational drugs. Physiological habits (urine, stools). Exercise. Diet quantitative and qualitative. Allergy to medicines and other types of allergy. Previous gynaecology and obstetric history. |

2. Cordial greeting

Do we have to shake hands with the patient? Shaking hands forces us look at their face and smile at each other. Only with that will we mitigate certain aggressive behaviours of the patient. On the other hand, it is important to mention the patient by name and smile. These are two basic markers of cordiality, which we studied in Chapter 1. Control your non verbal communication in the first few minutes of interview: ‘do I look tired?’ ‘Do I look distant?’ If you control your body language it controls your most intimate emotions.

Importance of the first minute

The symbolic value of the first minute of the interview is beyond doubt: it involves recognising the patient as the centre of the clinical act, not the papers or the computer screen. Avoid interference of any kind. For example, before answering the phone or checking the patient’s past medical history, we can say: "Please excuse me for a second". As simple as that. And writing? We recommend documenting the notes while the patient is undressing for physical examination, after this, or when the patient leaves. Writing a lot is not equivalent to higher quality, because there is the risk of information saturation and not being able to process the ‘truly important’.

Let’s look a little closer at this fascinating process of observation, listening and verbal and physical examination. How does an expert interviewer work? At the same time the interviewer strives to create a friendly atmosphere and watches carefully how the patient introduces himself. Details of the patient’s behaviour speak to the interviewer can convey certain meanings (Table 2.2).

|

Table 2.2. Everything about the patient speaks to us |

|

|

The way the patient comes into the room: |

|

|

Difficulty of the patient in opening the latch Direct gaze, smile Look at the ground, surrounds the chair Defiant gaze, furrowed brow Periorbital musculature laxity |

Suspect apraxia, which may be related to cognitive impairment co-operative Avoiding conduct, interest in delaying the onset Anger, extreme concern Sadness |

|

How the patient sits: |

|

|

On the edge of the chair Reclined Arms on the table (invading space) Crossed arms/legs Gesturing to get up Limp, hypotonic |

Discomfort, uncertainty and anxiety Indifference Security in him/herself, drawing attention from the clinician Defensive, uncomfortable Avoidance, wanting to finish Sad, depressed |

|

How the patient speaks: |

|

|

Attentively, synchronously Restless eyes, voice trembling, voice falsettos Sad eyes, final exhalation phrases, "disconnects" as if ruminating about what they are saying Clenched fist, jaw clenched |

Cooperative Anxiety

Sadness Anxiety, anger |

|

How the patient responds to questions |

|

|

Hesitantly, covering their mouth, repeated gestures Signs of anxiety, slight expressions of anger Mild cough, patient touches their neck, earlobe or nose |

Insecurity Displeasure Avoidance |

|

Modified Borrell F, 1989 |

|

Delineating the presenting complaint. Map of demands and complaints. Pathobiography

The difference between a demand and a complaint is the expectation that professional may or may not be the solution. For example:

Dr.: What brings you here?

P: To see if you could do something about the pain in my neck, because of the ringing in my ears I don't want to say anything.

Demand: 'solving the neck pain'. Complaint: ringing in the ears (the patient has no expectation of resolution). Sometimes it is appropriate at this point to make a map of all demands and complaints, as a global drawing can provide data for the diagnosis. Here's how the dialogue would continue if the professional had the purpose of making a map of complaints:

Dr.: Tell me, please, what other discomforts do you have?

P (a little puzzled): because right now don’t you know what to say...

Dr.: For example, how is the rest of your body?

P: Now that you ask, my arms and legs hurt... I have not been the same for the last two to three months. I feel quite tired.

Dr.: and how is your sleep at night time?

P: I sleep well at night, but then I feel tired all day.

Dr.: how is your mood at the moment?

P: Fine, it is fine. If it wasn't for this fatigue I feel, it would even be positive.

In general, an inexperienced interviewer tries to focus on a single reason for the consultation, and is even intolerant to people who provide various reasons for attending ('today I will address the neck and another day we'll assess the tiredness'). We suggest otherwise: we propose making a map of complaints and demands as complete as possible, because this is the only way to get to the bottom of the patient's problems. In the case exemplified above, note that the patient is drawing us an asthenic syndrome with multiple pains without any data that guide us to depression. Therefore, it is imperative to find out if there is also anorexia and weight loss, and other information that excludes a systemic illness. This orientation was not so obvious if we had focused exclusively on neck pain.

Pathobiography is another useful technique in confusing demands. We recommend it especially when the patient assumes that you have information that you don't actually have, or when you have started a possibly incorrect way of approach. For example:

Dr.: Your blood results are perfect.

P: So, I do not understand what is happening to me. Every day is getting worse and I am having more pain each day. Oh, and remember when I mentioned that my leg gives way? Sometimes in the morning I wake up and I fall because my leg does not support me. I told you this, but you ignored me.

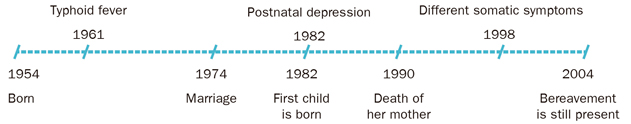

At this point the doctor is confused because he has absolutely no recollection of the patient mentioning this topic. They may be tempted to settle the demand with a symptomatic prescription, but it would be a mistake. Later, when they mentally review what has happened, they would realise that the patient’s problem is poorly resolved. For this reason you may prefer to start from scratch, applying the pathobiography technique. So, he draws a line that is based on the patient’s date of birth patient and he reviews the chronology of all the patient’s medical problems, including the current illness. For example:

Dr.: Let's recap from the beginning. You were born in 1954; did you have a happy childhood? Did you have any major illnesses? When did you move to live in the city? How did you react to the birth of your first baby? Have you had similar symptoms previously? and now, when did you start feeling unwell? etc.

See Figure 2.2. This pathobiography includes the case of a woman who starts feeling depressed after giving birth to her first child, it deepens with the death of her mother and currently she presents with different somatic symptoms. When working out the meaning of the current illness, this data structured in a visual format will undoubtedly be very useful.

|

|

Figure 2.2. Patient Eugenia B's pathobiography |

Exploring beyond the apparent presenting complaint

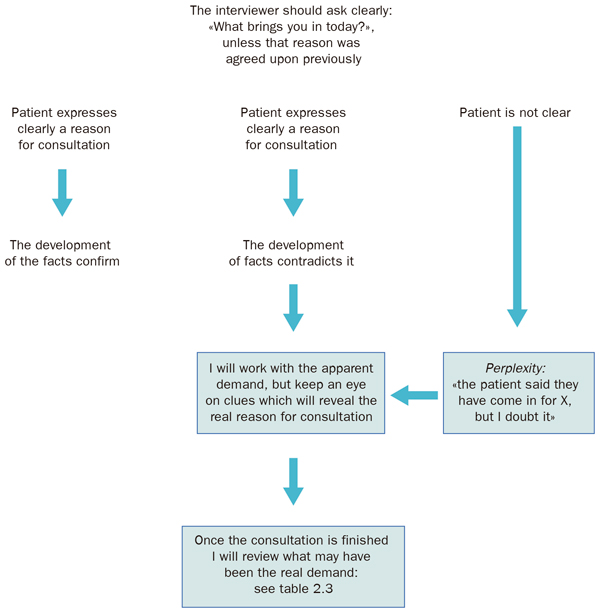

The reason the patient declares for consulting is not always what they really want to consult about. In Figure 2.3, observe the following decision of the clinical expert: 'I'm perplexed: the patient says they have come for X, but I doubt it'. The interviewer has reasonable doubts or is simply intuitive, so he puts the real reason for consultation on hold for some time. A clinician can take years to master the point of perplexity, because it is tantamount to admitting that 'I don't know the real reason for the consultation'. Know that we don't know. We fear not knowing because it is a form of weakness. But that is not the main difficulty. The main difficulty lies in continuing to work with a question mark rather than a certainty. Tell us: 'well, I don't know if this patient really comes to consult for his obesity, if he wants an emotional support or if he wants to take the day off, I don't know, but at the moment I'm going to work with the apparent demand'. Often new reasons for consultation appear at the end of the consultation (those reasons which really worry the patient), or specific demands which shed light on the whole process. In Table 2.3 we summarise some typical patterns.

|

|

Figure 2.3. What brings the patient to the consultation? Working out our 'perplexity point'. |

It is of the utmost importance to predict, beyond appearances, the real reason that brings the patient today and in this way to the consultation, because this either a good or bad use of time arises. One aspect which distinguishes our model is that we affirm that there can't be good listening if the professional doesn’t know how to manage time or misuses the time available. If we unduly lengthen the consultation and people start to complain about the delay, the professional will be impatient, may not be empathetic and won't be in the necessary psychological position to listen creatively. Knowledge of Table 2.3, along with time management techniques, will give us the assertiveness point to tell us: ' it is worth letting the patient talk without stopping him, I'm doing my job well, and will recover this time later'.

|

Table 2.3. Beyond the apparent demand |

|

Some reasons for consultation which appears beyond the 'official presenting complaint of the consultation':

Business card: 'I introduce myself with this demand (business card), but in reality, I will soon reveal, I come for a different reason that may be dismissed by the professional if I mention it directly'. Rationality: the patient believes that some complaints are received by professionals better than others, for example those which are somatic in nature, anxiety or psychological distress.

Exploratory demand: 'I come with an apparent complaint of a cold, but what really concerns me is a genital lesion that has appeared. If the professional who sees me is the same sex and is understanding, I will tell them at the end of the consultation. Otherwise, I won't'; Rationality: there isn't enough trust, confidence or knowledge of the professional.

Shopping: 'First I have to get an orthopaedic product. Then, if the professional is friendly, I will add to the order: something for dry skin, a box of painkillers, etc'. Rationality: fear that the professional will refuse these requests; the interest of the patient is to take full advantage of the benefits.

I will make him feel sorry (or I am going to play the victim's card): 'I'll tell him everything that hurts me to get a very good consultation and so the Doctor realises that I am not acting. Then, I will ask for a medical report with everything he can include, so that I can be recognised as having a certain degree of disability'. Rationality: attracting the professional's attention and compassion the patient believes they will achieve certain benefits.

Pulling his ears: 'Today I will lengthen in the consultation regardless of how many people are waiting, so he understands that I need to be treated differently and when I ask for a prescription, this is something I need. I will only go faster if the professional does everything I ask for'. Rationality: the patient attempts to attract the professional’s sympathy and model the professional's behaviour, so that they yield to the patient's demands.

Heal the soul: 'Everything hurts, my head, arms and legs ... let's see if fixing these bit by bit you heal my soul, which is what hurts more'. Rationality: the patient experiences an emotional pain that increases other physical pains, or their emotional pain is expressed as a somatic pain. In any case, the patient vaguely requests relief for their emotional pain which hides behind their purely physical symptoms.

I only come to let off steam: 'I know that I won't be cured, nor do I pretend to think I will be healed, but at least you know everything I suffer. I have enough from the consultation just by talking, I don't want advice that will not help anything'. Rationality: the patient experiences some relief by simply speaking, sharing and even transferring some of their emotions to another person.

I saw him in the street : 'I saw him on the street the other day and told to myself “it's been a while since I have been to see the doctor” and that is true, because I guess it's time for my blood tests, isn't it?' Rationality: this item alludes to the iatrotropic effect (Feinstein A, 1967) (Yatros: medical; tropes: to), to explain why a patient attends today and not yesterday. There may be more acute symptoms, they may have heard a story on television that has scared them, may have seen us on the street, or another good reason to attend may have arisen. |

Active listening 'the interview leak point' and the technique of "pulling the thread”

Asking a lot of questions doesn't mean getting more information. Due to this, we insist that in the initial stages of the interview, space for the patient’s spontaneous narrative must be given, as shown in the example on the next page, where facilitations, interrogative sentences, reflective sentences and empathetic expressions are combined.

The example illustrates what we call 'emptying pre-made information’. Everybody coming to a consultation will have prepared some information; have a plan that more or less says, 'when I get to the consultation I will say this and that', and even sometimes (although this is less common) will plan that, 'I should not say such a thing because I do not want to reveal that ...’ However, in the ensuing dialogue the person may lower their resistance, and can even hear himself for the first time. These are the 'emotionally deaf', people who don't know how to listen to themselves or elaborate their own feelings (low insight), unless it is in an actual conversation.

|

EXAMPLE: «PULLING THE THREAD», ONLY A COUPLE OF LITRES OF COFFEE A DAY, Abbreviation: I: interviewer; P: patient. |

|

|

SKILL |

DIALOGUE |

|

Interviewer leaves it to the patient to establish the reason for consulting. |

P: I feel very tired. I: I see, could you tell me more about it? P: Well, for the last month I don’t feel hungry, I feel dizzy and I don't feel like doing anything. |

|

Facilitation |

I: Mmmmm... |

|

Words/Reflective sentences |

P: I've trying red Korean ginseng, but it didn't work. I: Not at all? P: Not at all. Because my neighbour said it could be depression, and that ginseng works well for depression. But I don't think this is depression. I: Why not? P: No, I think this is exhaustion... |

|

Empathy + cordial order |

I: I understand... go on, please. P: For the last months it's been crazy at work: I wake up at 5 am and I go to bed at 12 am. It’s really bad... |

|

Interrogative sentence |

I: I wonder how you've been able to cope with so much stress... P: I have coped by using with stimulants … |

|

Words/Reflective sentences |

I: Stimulants? P: Coffee, and something else… |

|

Facilitators |

I: Tell me more please... P: Not strong stuff like heroin, but some joints... |

|

Find and complete data |

I: Do you spend ... say ... 15 a day? P: No, how awful!... no, sometimes if I go to the pub in the evenings and someone invites me I get to ten, but it is rare. Usually it is about three or so. I: What other stimulants do you use? P: I don’t use cocaine, I took some several months ago but not since. I: Coca-cola or similar? P: Just coffee, but quite a lot. I: What do you mean by quite a lot? P: A couple of litres per day. I: Mmmm |

These people can literally discover that their relationship is not good at the moment while they are talking to us. These are floating feelings which become more concrete in the act of asserting them as real. When the patient says, 'I think there is no love in my marriage', they not only note the lack of love, but also they allow him to make it clear. In this act there is always a certain amount of commitment: commitment to tell the truth, and make decisions in accordance with this new reality. We must be consistent with what we say. Therefore a way of not making decisions is not talking about our feelings! But unfortunately floating feelings are around, bothering to exit in a dialogue and explain to the patient himself and surprised. Is it advantageous to have insight? We said that the person with insight is one that can recognise their feelings. In general they usually achieve this by simulating dialogues (virtual dialogues), in the privacy of their own thoughts, imagining that they are talking with significant others. To have insight we must lose our fear to face what we feel. This is precisely one of the causes of emotional deafness: lack of sincerity or cowardice with oneself.

In summary: in the first minutes of the interview, the interviewer may easily miss some comments from the patient which are true rough diamonds. Either you recognise them or they may not reappear.

Textual reading and suggested addition techniques

Another useful technique in the diverse clinic patients is the textual reading of symptoms. It consists of literally reading the patient’s expressions in an, almost shorthand way and then reading them a second time as if they were from an unknown patient. This technique minimises prejudice (and stereotyping) in relation to the patient which could block our reflective capacity. Moreover, when addressing somatising patients it is always useful to collect the literalness of their expressions, as the patient often forgets them and they think 'every time' that their symptoms are new and they panic. Reminding the patient that 'these symptoms' were similar 5 years ago (and reading their literal expressions) could be of great help.

Suggested addition technique (Coulehan JL, 1997) consists of suggesting to the patient something we think they want to say but they either don’t dare or can't find the words for it. This is a technique commonly used by projective interviewers:

Patient: I feel I don't know ... with a nuisance …

Interviewer: Here, where are you pointing? In the chest?

Patient: In the chest and it moves here, but it is not strong, but…

Interviewer: But it scares you?

Patient: It scares me because I think it could be my heart.

Interviewer: Could it be because you knew someone who had something similar?

Patient: Yes, of course, my father.

It is a technique that accelerates the interview and used well, can support communication flow, but it has the risk of suggested interpretations or questions with induced response for example, 'could it be that you also feel more nervous lately?' The range of possible responses is very limited.

Fourthly, the expert interviewer while listening to the patient has already drawn a mental picture of the person and their suffering. On the one hand, he has a basic interview plan (developing some general tasks, such as, for example, asking how, when and where the main symptom appeared), but simultaneously he asks himself 'how would I feel in such circumstances?'. It is empathic listening in which he imagines how he would feel with the patient's symptoms.

Framing and reframing the interview. Resistances.

'What is expected of me?' The answer we give to this question in every moment of the interview is the framing or intent of the interview . For example: a mother comes to an appointment with the practice nurse to get some advice about healthy eating; the interview seems to be agreed between the mother and the nurse. But at one point of the interview the mother departs from the script and starts crying. The nurse is first surprised, then irritated (there are many people waiting), but finally she guess that she is in a 'business card' type (table 2.3) interview and she asks herself: 'what is expected of me?' 'Right now, it is just to listen'. So she does and the patient tells her about a serious marriage problem. The nurse asks herself again: 'what is expected of me?' 'I don't think she is waiting for advice, she rather prefers to blow off steam'. However, the patient states: 'Do you think I should leave my husband?' Again the nurse has to reframe the interview: 'what is expected of me?' To give advice for which I don't have enough information, or the necessary psychological training to help. Therefore, I must make it clear to the patient that we can't leave the empathic listening frame. I am not prepared for a counselling type interview.

Something similar happens in this other sequence: a patient says: 'I have come for a sick note as I have horrible bronchitis'. 'What is expected of me?' the doctor asks himself: 'a sick note for acute bronchitis, however, I can see the patient has lost some weight... I have weighed the patient and I note involuntary weight loss. 'What is expected of me?', the patient will be happy with just a sick note, but my professionalism compels me to explore this weight loss further; I am going to suggest some blood tests'.

In this second case, note that reframing depends not only on the patient, but it also depends on what the practitioner considers good medical practice, which can change in each moment.

Behind a framing of the interview there is a forecast of actions required and an estimate of the effort that these actions will require (LR Beach, 1990). When a diabetic patient tells the nurse that his feet hurt, the nurse immediately projects an image of herself getting up from her chair, taking off the patient's shoes and socks, enduring the odour of the foot, etc. What will this effort yield? she asks herself. It is likely to have a high yield as undoubtedly he may have neuropathic pain because he is diabetic. In contrast, the same complaint in a healthy young patient can be dealt by putting his feet in salt water.

Therefore, to summarise, see below the types of resistances to reframing:

-

Resistance to physical effort: for example, resistance to get up from the chair (the common situation 'could you take my blood pressure'), or going to a home visit ('now that I should go and see that palliative care patient, it starts raining cats and dogs').

-

Resistance to cognitive effort: for example, resistance to consider a psychosocial diagnosis when we were following and a physical clue ('what if that dizziness could be depression?' No, it can't be because that would put me in a difficult spot. Ugh, go away laziness). We are afraid to think about depression in a patient who has lost their appetite 'what if other more important physical problems are missed'. We fear ourselves that by looking into the psychosocial aspects too much, we may end up missing the biological side. In other words: we don't trust ourselves. We know that a seductive hypothesis, which sheds some light on the case, paralyses other searches and hypotheses. To summarise: precisely because we do not control the reframing, we allow ourselves to be pinned down by the first hypotheses which are formed in our brain, the danger of this is that it expressly forbid us from thinking about psychosocial causes until we have discarded the physical causes. We term the psychosocial 'hop' when we move from an organic hypothesis to the psychosocial ones, and we recommend making this 'hop' an automatic habit.

-

Resistance to emotional stress: for example, when we make a diagnosis by saying... 'I'm sure you have such a thing', and the subsequent data doesn't point in the same direction. On such occasions, we compromise our self esteem. The more proud, arrogant or petulant the practitioner, the more they will insist on his first hypothesis, as if rejecting it will dent their pride. Even the fact that we advance a diagnosis before finishing the interview, makes denying it harder for us. Never make a diagnosis in a hasty manner, give yourself plenty of time.

Mistakes to avoid

Attitudinal errors

* «I know what happens to this patient»

«Looking at how the patient comes into the room, I almost know what happens.» This comment can have some truth in it (a good observer is able to guess many things), but it also tends to be the result of laziness. One thing is to imagine from our reality, what happens to the patient (what Bennett MJ [1998] calls sympathy by memory), but the other thing is to get closer to their world, their beliefs, expectations and their ways of interpreting health and disease (this is what is called empathetic effort). This requires an attitude of not pre judging what the patient is going to say to us, even if this respect does not equal neutrality. We can disagree or confront their beliefs, but we should always be oriented towards patient's benefit (rather than 'who is right').

* «I am just a technician»

“Patients cannot expect empathy or warmth from me. This is not a consultation with a Psychologist. I can give them my expertise, but I'm not here to be their 'mum or dad', and I can't fix their life. I understand diseases, not human happiness”.

We have noted this discourse between doctors and nurses in hospital and primary care, and even among some psychologists and psychiatrists. It goes further in some clinical departments and the practitioner uses the method of antipathy or coldness, to the extent that some of these comments can be heard: 'Look what has happened with somebody, hence his (bad) manners'. For this reason we say that the current problem in the health care relationship is not paternalism, but coldness of the practitioner. Moreover, the criticism of paternalism can be an alibi to justify this new style of being cold and distant. Note the following comment: ' I give the information I have to the patient so that they can decide what to do. But I don't go explore their feelings or let their suffering affect me'.

This comment shows fear of the other person, to prevent friendly relationships that can 'appear' in the health care relationships. This style, in the model proposed by Emanuel EJ (1999), would be an aseptic advisor. Here is a typical dialogue of an aseptic advisor:

Abbreviations: D: doctor; P: patient.

D: One possibility is to have surgery; another is to continue using stockings and postural measures.

P: what would you do?

D: It is you who has to decide. I've already informed you of the percentages of success and failure.

P: I will go for surgery.

D: OK, but keep in mind that these varicose veins will give you problems.

P: What would you do?

D: My opinion is irrelevant. You should decide.

P: OK, I’ll go for surgery...

D: Of course, but I am stating that this is your decision, not mine.

P: Then, I won’t have surgery

D: You'll see... then you will develop phlebitis and you will see how much you suffer...

In any human relationship, it is impossible to set aside emotions and feelings. Caring for the patient, said Peabody FW (1984), can only be made from true positive affection, that solidarity emotional quality that we have agreed to call empathy. We are not asked to give kisses or hugs, we are asked for an understanding look, a word of encouragement, we are asked for a minimum sympathy which shows our concern for the patient... or is the patient is not entitled to it? It sometimes happens that the practitioner is concerned, but has not learned to transfer this to the relationship. A professional concerned by a patient can appear distant or cynical. We come from a culture of modesty that makes it difficult for us to put our feelings on the table, especially when they are positive. However, doing so in a way which is honest, is an important step in building trust.

Whether we want to be or not, we are part of the influences that the patient wishes to receive. That’s why they come to see us to our clinic. We are also qualified like few others to give personalised advice, and even to take certain risks. Of course, the background tone will always be to be respectful of the patient's beliefs and decisions, but this does not preclude the fact that part of our job is to put the best decision (and the best of ourselves) at the service of our patients. In the example above:

P: What would you do?

D: We starting from the basics, firstly, you are who decides, because only you know the fear you have about surgery, and your work and family conditions, etc.

P: Yes, but...if I was a member of your family, what would you recommend?

D: In this case, I would recommend going for surgery, because the progression of your legs will be bad, and there is a risk almost certain of thrombophlebitis and other complications in the long run. There is also the surgical risk, of course, and the frequent risks include, those of general anaesthesia... (they are listed). From my point of view the balance between the risk of going for surgery or not going to is positive for surgery, if you assume that there is a general anaesthesia added.

P (after thinking about it): I think I won't have surgery. I would have to give things much more consideration before having an anaesthetic.

D: It is a decision which I respect. If you change your mind please do not hesitate to contact me.

* ' Arrogant ' attitude

The patients have to do what they are told. When they are caught red-handed straying from their diet or not taking their pills, it corresponds to scolding them. This attitude can be accepted by certain patients, but can generate a strong rejection in others. Scolding is one of the most constituent acts of a paternalistic relationship. But it may sometimes be necessary, as evidenced by the comments of some patients: '(practitioner) he became very serious and he rightly told me off for not taking the pills'. However to argue; emotional and pragmatic conditions must be fulfilled. When we get angry because a patient does 'what they please' we must calibrate the part of anger that corresponds to our sullied self-esteem and the part of anger which corresponds to the damage the patient has inflicted on himself. We can only argue with the patient for the second part, the first one must be neutralised. The pragmatic condition is that, additionally, if we argue because we believe that the argument will serve for something. Sometimes we are aware of that we reprimand without it having any effect on the patient, but we do it to unburden ourselves of responsibility ('I already said it').

A professional who argues a lot may have a guilt inflicting style. This style is often learned in the family background. When we have grown up in this environment, interpersonal relationships resemble a game of fencing, where each party takes 'advantage or disadvantage' on a score sheet with its 'credit and debits. Clearly part of every human relationship involves elements of 'giving and receiving', but we go wrong if that's what prevails. 'You must have done...' 'Where are we going if you don't take this seriously?' It matters little whether the professional is right or lacks reason, what matters is the climate it creates in the consultation. Should we therefore give up 'arguing' with patients? Not entirely, but when we do so, in general this should only be very rarely and we should do it for the patient’s benefit and not to fulfil our own emotional needs.

* Ignore our areas of irritability

Each professional has areas of irritability in their interpersonal skills. It is good that you know your own areas of irritability (Table 2.4).

|

Table 2.4. Trigger points that often irritate practitioners and how to transform them |

|

Patients who, at a certain point, say: 'and you, Miss, are really very young.' Internal dialogue that these patients promote: 'How absurd. Does not he realise that I am a doctor? He says this to annoy me.' Smart response: ' I will tell him with a smile and without sharpness: no, if I am a doctor/nurse, didn’t you know?'. |

|

Patients who request further investigations or specialist referrals, before we have been able to assess the problem. Internal dialogue that these patients promote: “Can’t they wait until I’ve worked out what the problem is first, the good Doctor that I am'. Smart response: 'Let's look at your problem first'. |

|

Patients who think we 'do nothing well'. Internal dialogue that these patients promote: 'If I’m doing things so badly, please change practitioner. Smart response: I will say, 'I realise that you are having a hard time at the moment' and I won't take it as a personal failure. |

|

Patients who are very talkative. Internal dialogue that these patients promote: what a selfish patient! He is not able to listen. Smart response: 'He must feel very lonely; I am going to listen to him for a while t try to relieve his loneliness'. |

|

Patients who won't leave the consultation room . Internal dialogue that these patients promote: But don't you see that I am tired and your time is over? Smart response: 'I will get up from the chair and guide him to the door in a polite way'. |

If we don't know our areas of irritability, we expose ourselves to a daily and persistent emotional drain. The skills of a clinician are built on a daily basis, and by no means as a runner on a 100 metre sprint. Everything that wears down the quality of our professional life must be analysed and reviewed and first and foremost our own negative emotions. Does this mean that we must not express our negative emotions? We can do it when:

-

We do this for the benefit of the patient and not as an outlet for our own emotional stress.

-

At the end of the interview, when we have already reached a therapeutic agreement or in any case when we've already figured out enough data to form an idea of the patient's problem.

A healthcare relationship presided by feelings of mutual collaboration is named 'being in emotional flow with the patient' (Goleman D, 1996). Here are some tricks to get into emotional flow:

Abbreviations: P: patient; D: doctor.

P: You always give me these tablets, but I what I need are x-rays.

D: I will take this into account. I always appreciate hearing what the patient believes is necessary to do. What about moving to the couch for a physical examination?

The practitioner has used a technique called intentional assignment. He does not give in immediately, but 'takes the information into account'. Only with this will be patient be relieved of some of their anxiety. Another patient comes in this way:

P: Oh no! The practice has changed doctors again! That's not very helpful, is it?

D (with a smile): I understand your anger (Renewal by objectives): However, as we are sitting here together now, I am going to ensure that your effort to come and see me is helpful. What can I do for you today?

In this case, the practitioner has implemented a renewal by objectives: moving the subject onto what the content of the interview should be.

In this case, the practitioner has implemented a renewal by objectives: moving to what the content of the interview should be. But do not confuse 'being in flow' with 'sucking up to somebody'. At times, fortunately only occasionally, the patient can be rude and crosses the border of what is acceptable. It is not easy to determine when this happens, because we are talking about patients with significant stress, or with cognitive impairment. A clear and malicious intention to damage our reputation or damage us repeatedly can draw the line, and make it convenient 'to distance ourselves from the patient' or even propose a change of practitioner. Here is a way of ending a professional relationship with a patient suggesting to the patient that they change to see another Doctor: ' I find very difficult to continue having you as patient in these circumstances... have you considered the possibility of changing to another practitioner?'.

Technical errors

We collect the Table 2.5 more frequent technical errors in the exploratory part of the interview:

|

Table 2.5. Technical errors in listening |

|

Non-existent or a very cold greeting. A lack of cordiality. Bringing in a reason for antagonism at the beginning of the interview. Not attentively listening to the phrases used by the patient at the time of coming into the consultation. They sometimes contain key elements which subsequently do not appear later on. Not clearly establishing the reason (or reasons!) for the visit. Assume it or accept vague explanations. Introducing elements of health education when we have not yet finished taking a full history. Premature reassurance. Not integrating the information obtained with the existing problems and diagnoses that we have in patient's medical history. |

* Non-existent or a very cold greeting. A lack of cordiality. Bringing in a reason for antagonism at the beginning of the interview

Example of lack of cordiality:

Abbreviations: P: patient; N: nurse.

P: I have this headache that I can’t live with! By the way, is there anything new for osteoarthritis? I'm in agony.

N: let's see, if we skip from one subject to another I can't clarify anything in my mind. Firstly, the headache, okay?

The right thing would have been:

N (sentence by repetition): You came for the headache, but it seems that your body is in pain. (Map of demands and complaints): Tell me all the body parts that hurt...

Example of premature antagonism:

P: I'm here as I need my repeat prescriptions. The pharmacist has already issued them in advance.

E: I don't do prescriptions in advance, in any case, I see patients.

The right thing would have been:

P: I'm here as I need my repeat prescriptions. The pharmacist has already issued them in advance.

E: Is there anything else you would like to ask me today?

P: No, just that.

N: This prescription is for an antibiotic, why are you taking it?

P: I have a urine infection. I know the symptoms and to not waste time I went directly to the pharmacist, I did well, didn't I?

N: What were the symptoms that you noticed?

After finishing the history taking and, if necessary, the examination, we will explain practice rules in relation to advance prescriptions by the pharmacist.

N: Indeed, it seems you have had a urine infection and that the treatment has been effective. You must complete 7 days of the treatment. On the other hand, our practice rules prevent us from doing advance antibiotic prescriptions by the pharmacist. This is due to there is a tendency to self-medicate with antibiotics in this area, and this can cause the medication to become less effective. For this reason we have received instructions from that once we have warned the patient, we can’t do any advance antibiotic prescriptions, because we always have an emergency service at your disposal 24 hours a day. As this is the first time you request it I will do this prescription, but please bear that in mind?

We understand by antagonism (Froelich RE, 1977, p. 29) that verbal or non-verbal conduct that opposes, criticises, blames or contests the conduct or the emotions of the patient. Its most common formulation is of blame: 'why didn't you do what I've told you?', 'if you don't lose weight I don't know why you come to see me', 'I don't know why I teach you gymnastics if you don't stop smoking', etc.

Blame is a more defensive than an aggressive weapon. A demand perceived as 'dangerous' (for example, a lady who comes in complaining: 'everything that I have told in order to get better, is not working'), it is deactivated with an attack ('how do you expect to get better if you don't follow the diet correctly?'). However, the advantage achieved by the practitioner occurs at the expense of creating tension. The deterioration in the clinical relationship affects an anti-placebo effect. The patient may wish that ‘what he has been told' doesn’t go well in order to return to 'protest', more vehemently.

Does this mean that we can' criticise patients? There is no doubt that sometimes a frank criticism (for example a criticism of a behaviour or a dangerous habit) should be considered as part of our responsibilities as 'carers'. In these circumstances we should observe some rules for constructive criticism:

-

Criticism must be made in an appropriate environment, without the patient thinking that we underestimate him or that 'we punish him'. From the beginning it should be made clear that it is constructive criticism with an operational purpose: improving his health through better collaboration.

-

Tone and voice, as well as vocabulary, should be the same standard as for any other health advice.

-

If we are tense inside due to the 'misconduct' of a patient, we might try to 'punish him' even without explicitly wanting to. The technique of self-disclosure (Duck S, 1981, p. 42; Headington BJ, 1979, pp. 64-72), which translates as ' showing / discovering our own feelings' and consists of telling the patient how we feel: 'I feel bad that you haven't taken everything we talked about the other day seriously', 'I take great a interest in your case, but I feel as if what we are talking about, you are not with me', etc. To some extent this is showing our fragility, but this point of fragility makes us more human in the eyes of the patient.

-

We must always leave the door open to the patient for an airy and positive output. Do not aim for an act of contrition!

*Not attentively listening to the phrases used by the patient at the time of coming into the consultation. They sometimes contain key elements which subsequently may not appear later on.

Example: 'I come because of this horrific dizziness and a buzzing sound in my ears. Oh, and I feel very anxious'.

The practitioner focuses on the dizziness and the tinnitus, when the key to properly resolving the interview was in 'I feel very anxious'. If the practitioner at some point in the interview just said: 'and this feeling of anxiety that you mentioned?’ it would have opened doors for knowing the psychosocial distress causing (or amplifying) the dizziness.

Beware! One of the most common misdiagnoses is the inability of the clinician to establish what we call double diagnosis. It consists of establishing as a cause of the patient's suffering due to not only a single cause in either the organic or psychosocial area, but two or more causes, either in the same area or in different areas. A double diagnosis would be:

-

Patient with reflux symptoms and epigastric pain due to: oesophagitis with hiatus hernia, duodenal ulcer, H. pylori positive, and anxiety due to stress at work.

-

Dizziness due to viral labyrinthitis which started 2 months ago and gets worse due to generalised anxiety disorder.

Actually a very high percentage of diagnoses should be double diagnosis, and, as shown, just think about any symptom felt by ourselves and different diagnostic categories we could apply. Are you known for being baffled? In this case, you are a greater risk of these types of misunderstandings:

* Not clearly establishing the reason (or reasons!) for the visit. Assume it or accept vague explanations.

Are you known for being baffled? If this is the case, you are a greater risk of this type of misunderstanding:

P (comes in complaining of a dental abscess that has slightly deformed her face): I come for this headache (pointing at the dental abscess when the doctor is looking at her medical records), that has scared me.

N (focusing too early): This headache, is it present in the mornings or in the evenings?

* Introducing elements of health education when we have not yet finished taking a full history. Premature reassurance.

Imagine a patient who comes with cold symptoms and the practitioner asks in the exploratory phase:

D: Do you still smoke?

P: Yes, I do.

D: So, if you continue smoking everything we could give you won't work. If you don't think about it seriously, we can't go anywhere.

The intervention itself may be correct, but try not to interrupt the exploratory part with tips or instructions (unless they are very specific). The exploratory part of the interview requires a climate of special partnership, and if we interrupt with advice we may make the patient become defensive.

Premature reassurances are a type of standard response: 'you will see how everything gets better'. It is almost a cliché to mitigate our own tension which we experience when a patient starts crying or tells us bad news. It is to prevent us getting involved in the subject and it is equivalent to an educated rejection, something we have learned in our social encounters (Bernstein L, rejection 1985, pp. 65 et seq.). When we meet an old friend and we ask: 'how are things going?’ we hope that his answer is going to be invariably: 'well, thank you'. To such an extent we meet this ritual is that a popular joke is that the person questioned answers: 'well, thank you, or do you want to hear the truth?'

What should we do when a patient tries to make us partake in their suffering? Here are some recommendations:

-

Find out the characteristics of the patient’s problem: 'what makes him feel this way?', 'how is the partner taking this situation?', 'what plans does he have to improve the situation?', 'how does he think I can help him?' etc.’ If you don't have time to do so, or the consultation was already finishing, you could rehearse: 'do you think we should see each other again with a bit more time to discuss this problem further?'.

-

Some health problems have few solutions, for example: irreversible blindness, chronic illness, etc. But even in these cases, all problems have two aspects: a) the problem itself, and the possibilities of improving it, and b) the way in which the patient can cope with it, and adapt their life to it. Don't be influenced by the patient's pessimism, but on the other hand, ask yourself: how would a person with an optimistic frame of mind react in the same predicament? Even in the worst case scenario, a supportive empathy will always be possible (and no 'assurances'), and can be expressed with a glance or a gesture (Tizon J, 1982, 1988).

* Not integrating the information obtained with the remaining problems and diagnoses that we have in patient's medical history.

The patient tells us some symptoms they have as if they are new, but they have actually already reported them a few months or years ago. But the worst case is that the practitioner doesn't realise this and duplicates investigations. This would be avoided if we were able to integrate the data from the clinical history (remember the open epicrisis method)

Situations gallery

We will see in this section:

-

When listening hurts

-

The patient with multiple complaints

-

The intruding relative

-

When the doctor and the patient speak different languages

When listening hurts

In the first example, the practitioner attends the carer of a terminally ill patient. The process stretches and ambivalent emotions appear.

Example: a carer on the verge of giving up.

/1/Family member: It is an unbearable situation. I'm about to explode.

/2/Nurse: You have to hold on. You will have time to cry later, but now you have to hold on a little more.

/3/Family member: I feel very unwell because I can't do anything, I can’t keep her well, and I can’t bear to see her in so much pain until she dies.

/4/Nurse: You don't have to think about death. Your mother can still live. While there is life there is hope.

Comments

1. What are the successes and errors in this brief conversation?

In /2/ the nurse says at the beginning: 'You have to hold on. You will have time to cry later, but now you have to hold on a little more'. This intervention can't be considered wrong, if done with enough empathy. Interestingly, the opposite intervention can also be correct, namely: 'you are doing well in expressing your feelings. If you have to explode, explode; cry or shout if you want to. You have every right in the world, because you are dealing with a lot’. What determines whether to use one approach or the other? One is suitable for carers who have the facility to cry (and even do so frequently), and their problem is rather to have the courage to face the hardships. The other one is for carers who are very contained.

In /4/ nurse said: 'You don't have to think about death. Your mother can still live. While there is life there is hope'. Here we can say that mistakes have been made. It is useless denying death and giving false hopes, particularly when the carer is trying to adopt a realistic position. When the practitioner has not assimilated that the patient is dying, when he is afraid, they may reinforce attitudes of denial by repeating typical social frames. From this arises containment capacity as a way to hear what the patient says which does not necessarily lead to giving advice ('you should...'), or an action. To have containment, we must distinguish between my way of being from the patient’s way of being. Containment gives a quality of quiet listening. It must also be clear that we do not always need to give advice indeed advice may also have its own iatrogenic effect.

2. Should we disagree with the carer because she indirectly expresses that she wants her mother to die?

Quite the opposite. It is normal to carers be torn between their affection for the person and the pain they experience by seeing the person suffer. You cannot avoid thinking about the relief that they will experience when the patient dies, and that arouses feelings of guilt. The practitioner can normalise and legitimise their feelings: 'it is very normal in your situation wishing it all to end, because it is very painful to see a loved one suffering so much; A lot of people in a similar situation to you feel like this’.

What should we do in such situations?

In these cases the most important thing is our manner in front of the patient rather than the words we use. It should be warm, close, comprehensive and, above all, calm. If the practitioner is behind a desk, they should move their chair next to the family member. Here is a dialogue demonstrating the interviewer legitimising and normalising the ambivalent emotions of the carer:

/1/Family member: It is an unbearable situation. I'm about to explode.

/2/Nurse (empathises, pausing briefly to give the interview a slow pace): You have taken on too much responsibility and work at home for quite some time.

/3/Family member: I want to cry, I want to shout, but I can't...

/4/Nurse (enables and supports emotions): Even if it’s only to say what you’ve just said, it is good for you, as you are venting a little ...

/5/ Family member: Sometimes I feel I am a bad person because I would like it all to end, and that they will no longer suffer.

/6/Nurse (legitimises): When you love someone and you see them suffer, you have every right to say that your emotions are stretched

/7/Family member: But I have no right to think about his death.

/8/Nurse (legitimises): These are very normal thoughts, especially when the burden of the whole situation falls upon you.

/9/ Family member (sobbing): He has always been very good to me, and I now think that it would be better if he was dead.

/10/Nurse (offering a tissue, drawing importance to the emotional ambivalence): What counts is not what you think, but what you are doing. (Increases self-esteem): Your role has also been essential. If it had not been for you, he would have been admitted to hospital and he probably wouldn’t have been as well looked after as at home. Not that you should have any doubt about that.

|

Remember, situations when listen hurts:

|

The patient with multiple complaints

Patients attend health services an average of six times a year. However, 20% of patients consume 60% of our material resources (time, medication and investigations). The current trend is to consider that all of them have good reasons to do so, and that, in any case, the challenge to lower their frequent attendance and multiple complaints, falls upon the health team. Note this first scene:

Example: The patient with multiple complaints

Abbreviations: P: patient; Dr.: doctor.

P (taking out a list): Doctor, today I’ve brought you a written list, because I always forget things.

Dr. (with a tired tone): I don't know if we will have time for so many things madam...

P: I feel very poorly, you will see Doctor, I can't continue like this...

Dr. (showing signs of impatience): Let's see, what can I do for you today?

P: Firstly, I have the issue about my kidney stones. I am taking calcium and I think that if I have kidney stones, calcium is not very good for them, is it?

Dr.: Of course it is alright, there isn't a problem with it.

P: But I've heard that...

Dr. (impatiently): It doesn't matter what you have heard, because I’ve told you there isn't a problem. Let's move onto another problem on the list.

P (grumbling): Ok, well, I have a cough, but I already feel a bit better... (suddenly changing tone of voice to another more cheerful one) Oh, by the way, doctor, I'm sorry, but today you will have to look at my bum.

Dr. (somewhat perplexed): why is that?

P (cheerful): Because I have piles like never before.

(Doctor proceeds to do a rectal examination. Returning from the examination couch)...

P (with the list in hand): Wait, doctor, I have several other things, I say this because if I sit down then I will feel too tired to get up again.

Dr. (puzzled): Well, we have looked at two points of the list today, we could look to another two points another day.

P (desperate): but the main reason I was coming today was about this dizziness and because the pharmacist has found my blood pressure to be 210!

Comments

-

Is 'one presenting complaint per visit' correct?This aphorism of 'one problem per appointment' leads to the patient's frustration and doesn't allow the doctor to get to the bottom of the problem. Consultations are multiplied in a climate of insufficient understanding and are less effective. As we said previously, the practitioner should make a map of complaints and demands, because this bigger picture of the patient will help him, to understand the patient to a greater extent.

Well, once we have defined that there are 'several problems' which we are asked to address, we will proceed by addressing each one in sequential order to its resolution. We will open an episode of disease for each of them (provided that you understand that they are separate issues), and if we don't have enough time to address them at the appointment, we will offer the patient a further appointment.

-

What is the main mistake of the practitioner?The main error is the tired and irritable emotional tone he shows. The patient feels vulnerable and their pessimism is reinforced. This leads them to arrange another appointment soon to clarify many of the points on their 'list' which remain unclear. The emotionally proactive practitioner (Borrell F, 2002) remains calm and even injects optimism into the relationship: 'I see you look very well, Sarah' 'congratulations on these blood results, they have come back as if you were 20 years old'. This type of phrase, when said by a 'super scientist' practitioner, connects with the symbolic world of the patient and may change their perception of their well-being. This should always be done on the condition of not lying, not even if well intentioned. Don't forget that often being healthy is not as important for our personal happiness as believing we are healthy.

-

Is there any significance to the way in which the patient introduces her requirements, and in particular the request for a rectal examination?In general, patients give us an 'agenda' and a few pre-write what they wish to be the content of the visit. The order and meaning of these demands should not go unnoticed. The patient has scheduled a longer visit than the doctor is willing to grant. For her it is a ritual in which there is an important social component. She wants to 'be able to explain' and possibly in her mind she has imagined a gentle and loving conversation with her doctor. This pattern is typical of lonely patients, in which a visit to the doctor or nurse is a form of socialising. The change in tone with which she announces her request for a rectal examination may be to mitigate her modesty, or could be to accommodate some erotic tension. Both possibilities should be taken into account, since in communication, it is always preferable to consider several hypotheses, simultaneously in a flexible manner, rather than a single one.

-

When the patient comes back after the rectal examination she introduces what appears to be her main concern... How should her doctor proceed?

First, the doctor must detect their own emotional reaction; undoubtedly this is not to re-open the interview. They should also assess the implications if what the patient says is true. It is precisely in situations like these where a good deal of flexibility marks the difference between committing to ones initial reaction and avoiding a clinical error. Measuring her blood pressure will take just a few minutes. Not doing so, on the other hand, may activate later anxiety: 'and if indeed what if she has a hypertensive crisis?' The personal cost of this anxiety is equivalent to a thousand times the small effort of taking her blood pressure.

¿What must we do in such situations?

-

Ask the patient to read the entire ‘shopping list'. Especially before asking the patient to get off the examination couch ask: 'are you sure we should not look at anything else?' If despite this, the patient pulls out another new request at the end of the interview (a request that doesn't make us anticipate any serious or imminent danger to the patient), we will suggest quite frankly: 'well, if this is ok with you, we will leave this issue for another appointment’. If the patient insists, we will clarify: 'unfortunately I don't have more time for you today'. It is very difficult to address more than... (i.e. the number of presenting complaints addressed here) problems in a single visit, so the best thing would be to arrange a follow up appointment with me for …'.

-

Differentiate the 'new' from the 'old'. These patients are at a high risk of clinical errors, basically because the professional applies the rule 'you come to see me about so much that I disregard you'. Another doctor or nurse who evaluates the patient without prior knowledge of them can discover disorders and diseases with a possible therapeutic approach towards them. Reconsidering these patients 'as if we didn't know them' tends to have a positive impact on the prevention of errors.

-

Try to regulate the frequency of patients’ visits yourself, and that both the medical and nurse appointments fall on the same day. Gradually reduce from weekly visits to fortnightly and from fortnightly to monthly. Use the phrase: ' I would like to see you in... days'. When the patient requests an earlier appointment without a compelling reason, don't refuse to see them, but then agree an interval until the next appointment which is acceptable to the patient.

-

Try to encourage elderly patients with cognitive impairment who come to see you very frequently, to attend with a family member or carer. Refer these patients to social services so that they can evaluate the patient’s need for support, aids at home, etc. Sometimes their visit reveals this deficit (which, incidentally, will never be revealed with a consultation).

Let's see these principles applied in the previous interview:

P (taking out a list): Doctor, today I’ve brought you a written list, because I always forget things.

Dr. (with a cordial tone): I welcome it. It is very good that you have come well organised. If you will allow me, we can read the list together.

(Both read all points of the list.)

Dr.: You have brought me 10 points, but hopefully, in the time we have today, we can deal with a couple or three of them... which ones do you think are the most important?

P: Doctor, all of them are important!

Dr.: Because of this I will arrange another appointment to see you next week, and we can address the rest then. Which point is considered the most important today?

Once two or three have been prioritised, the practitioner moves to solve them. The strategy of 'negotiating the demands in instalments', which we stand by here, does not contradict the map of complaints and demands outlined above. Although we postpone requests, the doctor has to have a full map of complaints, this is the only way to obtain good diagnoses. Imagine how hard it is to diagnose a patient with depression if we fractionate all the symptoms they have! For example, if at the end of the interview the patient adds:

P: oh! And my back! Aren’t you going to look at my back?

Dr.: Of course I will. Your back deserves a full visit. I would like to see you in 10 days, look I am going to book it myself, although I am very busy, for the day... We will assess your back and address two more points from your list. Is this day ok with you?

|

Remember, with a patient with multiple complaints:

|

The intruding relative

A strong biomedical tradition has demonised the relative, who by definition 'we need to silence' so the voice of the ‘real patient' can rise. This is a serious mistake which has led us to underuse a huge potential both establishing the symptoms and as a therapeutic ally. We are not we going to deny that the presence of a relative can sometimes be uncomfortable. See, for example, the following situation:

Dr.: How can I help you today?

John: I have a cold again.

John's wife: This is not correct, doctor. It is not a cold; it is bronchitis because he doesn't stop smoking. He ignores what you said. You have to scare him because otherwise I don't know when he is going to stop.

Dr.: Tell me more John...

John's wife: He spends all night coughing and because of it, I am not getting any sleep.

Dr.: Did you have a fever John?

John's wife: No fever, but the other day going up the stairs he got very pale, explain everything to him John! And he also had a pain here (pointing his chest). Come on John tell him everything! You shouldn't hide anything from the doctor. It would go against you if you don’t tell him everything, as he can’t help you properly if he doesn’t know everything.

Dr. (irritated): Madam, but don't you see that you have overwhelmed him, so there is no way he can say anything as he can’t get a word in?

Comment:

1. Do you notice any errors in the way the practitioner acts?

The last sentence from the doctor is undoubtedly sharp. He makes a judgement about the couple's relationship ('you have overwhelmed him'), and he gives free rein to his impatience.

2. Are there any key symptoms which were important in the previous dialogue?

Several key symptoms have appeared:

- The patient says he has a cold, he has cough but does not seem to have a fever (this point should be confirmed), and he is a smoker.

- Furthermore, it appears that the patient has had an episode of chest pain, perhaps associated with vasovagal symptoms.

- Finally, the interpersonal relationship of the couple is a useful data, as we will see below.

3. Can we deduce something about the relationship of couples who present in this way during the consultation?

The way a couple interacts is due to a relationship previously established and consolidated over the years. The practitioner will quickly realise who is in control of the situation, the degree of mutual dependence, the degree of appreciation and respect between them, etc.

In the case we are dealing with:

- Neither member of the couple could be so intrusive without the passivity, or concession, or secret interest, from the other member, to act in this regard.