Resumen

Índice

- Key Ideas

- Basic Skills in the first interview with a patient

- Before starting the consultation

- Establishing a therapeutic relationship

- Practical study: prevention of additional requests

- Mistakes to avoid

- Mistakes due to lack of control of the health care environment

- Mistakes at the start of the consultation

- Situations Gallery

- The patient with underlying aggression

- The patient with unrealistic expectations

- Establishing a relationship with a child as a patient

- Advanced Concepts

- Comfortable working

- The rational-emotive model. Fundamentals

- Cordial or empathetic? The importance of welcoming the patient

- Overwhelmed

- Preventing additional requests

- Recognising negative emotions

- The importance of a good doctor-patient relationship

- How do patients perceive doctors?

- Summary

- Bibliography

Starting a therapeutic relationship

Key Ideas

-

The emotional climate of a whole day's work is set in the first interviews.

-

Do not believe in bad luck or bad days: selectively observe the good things that this day is offering you, and see how this bad luck gradually goes away.

-

Overwhelmed? Or do you feel overwhelmed to be able to lament that you feel overwhelmed? Stop feeling sorry for yourself and focus on what you do, in every step you do! We must learn to live every moment completely.

-

You only have one chance to make a good first impression. But we should give patients a second chance. Attempt to make a positive first impression.

-

Are you driven by your first thoughts? Are you rather spiteful? Are there people that you; like or dislike' almost automatically? You have a reactive emotional style. We recommend you analyse what a 'proactive' emotional style is.

-

Law of emotional echo: you will get from your patients what you give during the consultation. If you give smiles you will receive smiles, if you give hostility, you will receive hostility.

-

Establish check points to monitor your own physical and emotional state. Use these “safety indicators” to detect tiredness or poor concentration particularly.

-

Learn how to identify your own emotions "listening" to your own tone, pitch and manner of speech.

-

Do not over value getting off to the wrong start at the beginning of a consultation. The interview is very fluid. At the end the patient may leave being enormously grateful.

-

Do you get overwhelmed as the consultation goes on? From time to time we have relearn how to enjoy the consultation.

-

From time to time we also have to relearn complex habits, especially the habit of being patient.

-

We are permanently in a state of unstable balance with our idleness, even our unwillingness to have patience.

-

Many emotions/feelings have an inertia (they become habits). Breaking this passivity starts when you overcome the laziness.

-

A good consultation starts with a good control of the environment and reviewing patient's past medical history. Integrating as much information as is available is half way there.

-

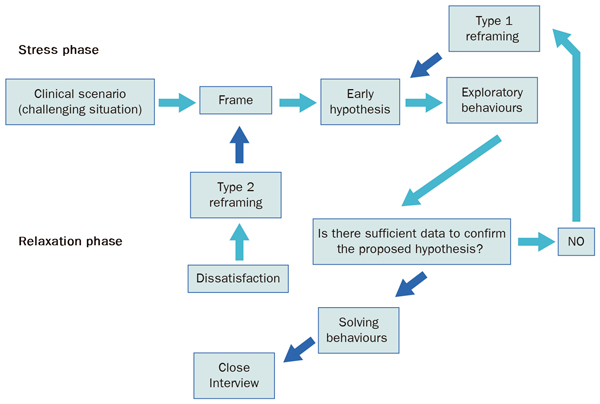

What is the aim for me to do here and now? The answer we give is the purpose of the interview. What happens to this patient? The answer we give is the early hypothesis. "This is incorrect; it doesn't seem that this patient has a urine infection”... This is type 1 reframing.

Basic Skills in the first interview with a patient

In the clinical interview (Cohen-Cole SA, 1991):

- Establish an interpersonal relationship.

- We perform a series of tasks to establish a diagnosis.

- We propose an educational and therapeutic plan.

Before starting the consultation

How is my mood and state of mind today? Am I awake and focussed or sleepy and confused?

These are key questions before starting the consultation (Table 1.1).

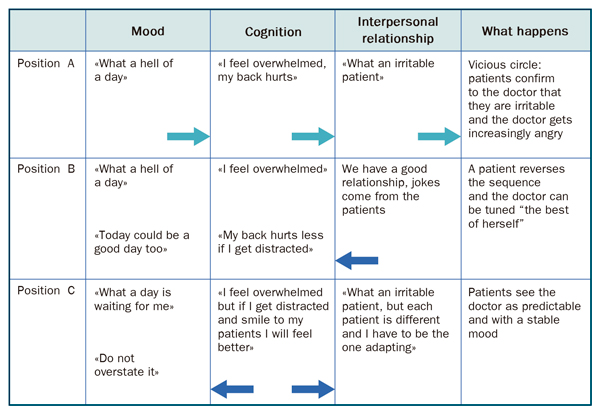

In Table 1.1 we exemplify self-fulfilling prophecies: “I feel bad, today is going to be a horrible day, everything is going to go wrong "... The origin of our bad mood can be situational (as illustrated), or due to physical or psychological distress. In any case, without realising we start working to be right, to give us a reason to have a bad day! So that the prophecy is fulfilled, we tell ourselves "no, I already said that, today I got out of the wrong side of bed". With this strategy, the prophecies, have some control over the outcome of each day. What a trick of magical thinking! But, is it inevitable? I don't think so. See Figure 1.1. In position A we see a professional unable to control their temper and their self-fulfilling prophecy. However, in position B the professional is sensitive to the environment. A patient jokes with the professional and transfers his good humour to them. Or it could be that the patient shows gratitude for a therapeutic success. The return arrow indicates that the process is reversed: the prophecy is dissipated.

Now we examine position C, which is much more interesting. Margaret realises that "I'm in a foul mood”."I have given to my son an antibiotic which it might not be necessary, just for my own convenience. I have messed my poor mother's morning". However, she thinks again: "Well, I did the only thing I could do, I chose the path of least harm, because otherwise I would have to take the day off work and leave my patients on their own and inconvenience my colleagues”. "Now I should try to ensure that this stress does not have an effect on my work. In order to do this, she consciously intends to smile to her patients. What is she trying to do? Firstly, receive a favourable emotional echo, which will reinforce a positive environment. If we are serious we will receive seriousness, if we smile we will receive cordiality (emotional echo law: we receive what we give). Secondly, the smile acts as physical training for emotions: it loosens up and relaxes the emotional arc, our ability to move smoothly by different feelings, without getting in the negative part of the emotional arc.

|

|

Figure 1.1. The circle of “bad days”. Black arrows symbolise the ability to reverse the process. |

Practical implications:

- Before starting the consultation ask yourself: how is my mood today? And my concentration? Sometimes, small emotional impacts have an exaggerated effect on our mood, and they ruin a day's work. Do not allow this to happen. Take care of yourself! (Neighbour R, 1989).

- Make an effort to be positive towards your patients. They are not "your enemies”, they are people who are fond of you. They are not “irritable”, they are seeking your help to ease some of their suffering. They are there because they trust you.

- Monitor your performance with some objective markers. For example, if you make handwritten notes, your handwriting will reveal your state of your concentration. Normally when we are very tired, our handwriting gets worse, the stroke is less regular. Fatigue also leads us to sigh, our eyes and hands experience a mild tremor and we may have to hide a yawn. Learn to detect these objective signs. If you detect them, apply the rules of the “safety indicators” as discussed in Table 1.2.

- Sometimes we say, "I am overwhelmed, I can't work like this!” but actually, it is a ploy to feel sorry for ourselves and to save us the challenge of giving the best of ourselves. When you think "I'm overwhelmed", say also: "Or am I making excuses for not doing things better?”.

|

Table 1.2. Safety checks when we are tired

James realises due to his handwriting that he is tired. On these occasions, he has several tactics to avoid making mistakes. Firstly, before the patient comes into his room uses his full attention to read the patient’s problem list (and the summary of their medical history if it is available). He documents pending issues (e.g. “requesting blood tests”, “health promotion”, etc.) directly into the patient's clinical records. Once the patient has explained their presenting complaints, he opens a section in his medical records for each of them (for each episode). For example: 1) headache; 2) thinks he may have wax in his ear canal; 3) control thyroid nodule. If the case is complicated, he prefers to write the findings of history taking and examination before resolving the interview (that is, before making a diagnosis he writes: “basal crackles, pulse 98 per minute, etc”). This allows him to buy time to think. While he is writing, his ideas seem to clarify a bit more. Finally he reviews twice the medications he has just prescribed, wondering: “Is it the right drug at the right dose?”. |

Establishing a therapeutic relationship

Before starting an interview:

Carefully read all prewritten data

As medical reports, medical records by other peers, but do not let them influence your judgments or comments like... “somatic patient” or “rude”, etc. Do this even with patients you already know. Refreshing your memory, with the intention of rediscovering the person in front of you is a very profitable investment. Objection: “I do not have time”. In this case, prioritise reading the list of problems or the summary and the last consultation.

Do not underestimate information from third-parties

They can be of great value as a source of data, and their opinion will influence powerfully on the patient. (That is why a patient brings a third-party such as a relative). The third-party is usually our ally, or in any case not our enemy. Objection: “What if the third-party doesn't let the patient talk?” Perhaps they are trying to protect the patient. Study some strategies in Table 1.3.

Try creating a warm and empathetic atmosphere

Do it naturally always. Do not force yourself to be more friendly or warm than you normally are, because when you return to your usual behaviour your patients will think: “why is he angry?” Objection: "how do I know that my tone is warm enough?” In general, one cannot know. Ask for some honest feedback from a good colleague or friend, do some video consultations and analyse them with an expert help or following the guidelines.

A warm welcome doesn't always entail a hand shake

Shaking hands helps, especially if you take the initiative. But it may be as or more important to look at the patient while we smile, or say their name. Try at least one "climate marker" in order to be warm; either a smile or a friendly comment, and especially your tone of voice. Our tone of voice often betrays us if we are tired. It is so subtle that a person can detect the degree of consideration they receive ... simply by the intonation of our speech!

|

Table 1.3 Accommodate a third-party who interrupts. |

|

“Interference emptying” strategy: Encourage the third-party to completely "empty" their anxieties, to tell us “everything”. Then we can say: “Thank you for this information, I will certainly take this into account; what do you think if the patient now explains how they feel?”

“The bridge” technique: the third party interrupts, but the professional does not restrict them, and asks the patient: “Is what your husband/wife has just said how you feel? "What do you think about what your husband/wife has said?”.

“Intervention deal” technique: “How about we let your husband/wife explain what is going on?”. If the third-party still interrupts, calmly and politely say “We decided we will let the patient talk”.

Technique of creating "another" environment: We separate the patient from the third-party. In some cases, we might say to the parent coming with a teenager: “Usually at this age boys/girls like to discuss things without the presence of their parents, not because they have things to say which they don't want to tell you, but simply because they feel more comfortable ... would you kindly wait in the waiting room, and then you can come back in?” Other times, we will indicate to the patient to move to the examination couch and with the third-party sitting in the chair we will continue taking the history. |

On the other hand, you can indicate friendliness by appropriately modulating your welcome to the patient. Objection: “Is it even possible to appreciate my own tone of voice?” As we said above, it is necessary to review our own video consultations and pay sufficient attention to our speech and mannerisms. You will see yourself tired, irritable, fed up, complacent ... due to the tone of voice you use. Pay attention to your own tone, pitch and manner of speech, it is the easiest and simplest quality control we have.

During the first minute, demonstrate to the patient that you are giving them your full attention. Look at them

Avoid performing other tasks during the first minute of the consultation, such as, reading the display on the computer or looking at the patient's medical records. This is not always possible, but if you must read the notes tell the patient: “you have priority”. Looking carefully at the patient does not mean staring at them, which will be uncomfortable. Objection: “What if before the patient comes into the consultation and I haven't had time to look at their medical records?” In this case you can say: “excuse me for a minute, I am reviewing your medical records”. And even “you had pneumonia at the age of 20, but have you had any other serious illnesses?”

Some patients may welcome some signs that they have some degree of control over the consultation

Provide control over processes For example: “Would you like a print out of your blood test results?”, “Would you prefer sachets or capsules”, etc.

Adequately establish the patient's presenting complaints

Find some appropriate techniques below:

- Define the presenting complaint: “What brings you here today?”.

- Preventing additional requests, “would you like to tell me anything else?”. Sometimes it is convenient to keep asking this question before coming back from the examination couch: “do we need to examine anything else which you haven't told me about?”.

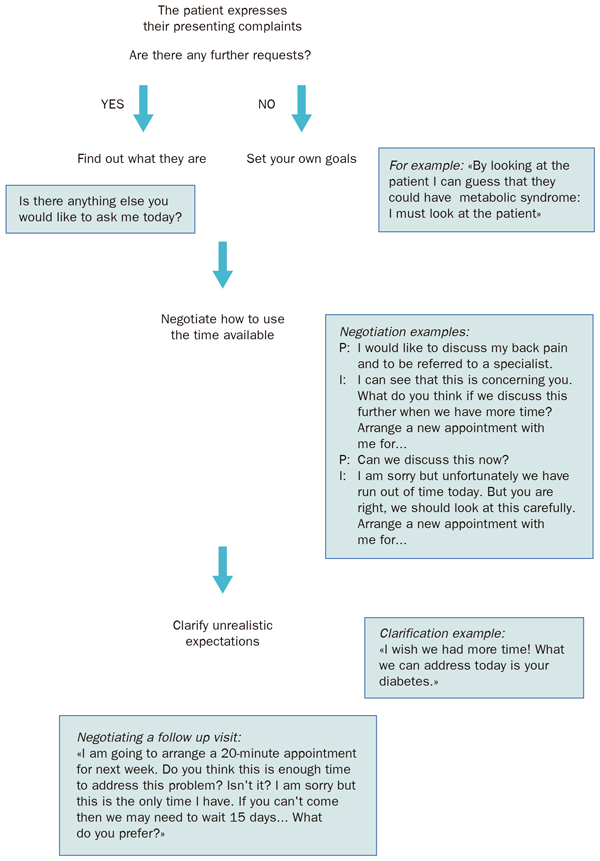

Note the use of these techniques in Table 1.4.

|

Table 1.4. Preventing additional requests.

Sarah knows her patients well: she knows which patients get straight to the point and which ones have a long list of presenting complaints. For the latter she has the following type of conversation:

Interviewer: What brings you here? Patient: My sugar levels, as usual, I can't seem to get it right. Interviewer: Is there anything else? Patient: My back, you know... the medication you gave me does not make any difference. Interviewer (trying to prevent additional requests): Is there anything else?

At this point some patients may say with a smile: “Don’t you think this is enough?”. Others may add some more complaints and, finally, there will some others who will try to “find something else”. Sarah's skill is to precisely recognise whether the patient really “had” something else. If she can't find something else she will finalise quickly saying:

Interviewer (making a summary of patient's complaints and organising the contents of the interview): If I understand this right, you have come today regarding your sugar levels and your back. Let's start with your sugar levels. |

Practical study: prevention of additional requests

You can observe below how a professional prevents additional requests and asks about past medical problems. Is it all done in the short amount of time we have? Indeed, because asking about these issues doesn't mean you should treat or solve them during this visit.

Tasks at the beginning of an interview

Abbreviations: I for interviewer and P for patient.

|

TASK PERFORMED |

DIALOGUE |

|

Warm welcome: at this point in the interview is crucial to look carefully to the patient and smile. So, it is important to review the patient's medical records beforehand. |

I (shaking hands): What brings you here? P: Many things and I don't know which one to start with. I: I am interested in all of them. |

|

Defining patient's present complaint: don't be afraid that the patient expresses everything on their agenda, because they are going to do it anyway. You have the advantage, of directing the process. See figure 1.2. |

P: I have wax in my ears, every year I have to get it removed, plus you have to request some blood tests and some other tests as I am due to be admitted to hospital for surgery on my hernia. My hair is falling out and I feel very nervous. I: Is there anything else? P: I have severe back pain that stops me sleeping at night. |

|

New additional requests prevention |

I: Is there anything else? P: It is long time since my last blood tests and you know my cholesterol level wasn't right. And every year I have a heart test. I don't know the state of this issue. I: Is there anything else? |

|

Negotiating the content of the consultation: the following statements can be helpful: “it is not possible to deal with everything today”. “We could deal with this topic when we have more time”. |

P (patient's stays thoughtful). I (doesn't allow the patient to improvise and think of new requests). Well, let's summarise: We will request some tests for your operation which will check your cholesterol. We will look at your ears, hair, back, and... |

|

The interviewer introduces his/her own objectives: Don't forget the following aphorism: patients who ask the most, ask anything but what it is really important for their health. |

…Looking at your medical history I saw you have been suffering from anxiety for a long time. This is something we should review further, as well as the heart topic: do you mind booking a further appointment for another day? Then we can look at these issues with the time they deserve. P: Yes, yes, of course. I: Great, then sit on the examination couch please. |

|

|

Figure 1.2. “Defining the patient's present complaints” |

Mistakes to avoid

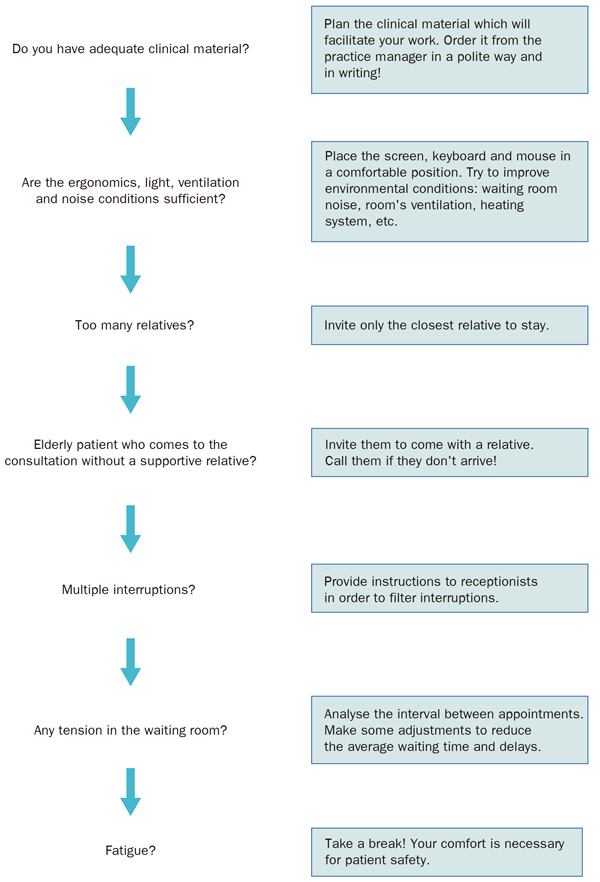

Mistakes due to lack of control of the health care environment

A good interview always start with a good environment management

Avoid consulting in the corridor or interrupting other work, or without having the necessary conditions to consult (such as having the patient's medical records, time and privacy). Arriving just in time to start the consultation is an error. There is always a patient who needs to be visited “first”, although they are not on the list (and sometimes it is reasonable to do so). Other times there may be blood results to review, prescriptions to sign, etc.

The control of the environment is key in home visits. On these occasions, the professional must ensure the maximum comfort: open the window to examine the patient with natural light, make the patient get out of bed when you can, have only one family member present in the room, among other measures. For example: “Could you open the window fully? More light will make it easier for me to examine you... And Mrs Taylor, can you sit on the edge of the bed (or in this chair) and put your shoes on? Are you the carer? Well, it is fine for you to be present in the room, please could the other people leave the room for the patient to have some privacy? Thank you very much” See Figure 1.3

|

|

Figure 1.3. “Master the clinical setting” before starting the interview. |

Provide “control” to your patients

Patients must be able to verify that they are on your appointment list on the date and time shown on their card, as well as whether their consultation is delayed, and the provisional time that they will be seen.

Ideally the patient goes to reception on arrival and there, they will get confirmation of their appointment and be informed of any possible delays.

Avoid arguing outside the consultation door

If there is confusion about the day and time assigned, this should be clarified by the administrative team responsible on the day and they should communicate to you any questions which arises. If there is an urgent inquiry from the patient, it is better to make the patient come to your room, and discuss this with them with the door closed.

Never deny care to a patient, but, the patient should adapt to your availability. For example, if there has been a mistake and the patient thought they had an appointment scheduled for today: “Of course I will see you, but we need to wait for a gap... at... (time)”.

Mistakes at the start of the consultation

-

Address older patients informally

Only do this at their request.

-

Do not define the presenting complaint or make assumptions about it

How are you?

How is everything going?

You’re here about your cough, aren’t you?

These all are bad starts to the consultation. The first two can be right only if the following dialogue clarifies things: “and what brought you in today?. It won't be the first time that after half an hour of talking with the patient about osteoarthritis, you discover that they only came in for a medical report for the gym”.

-

Sharp, impersonal, unfriendly and blaming communication

Here again?

Didn’t I tell you not to come unless you’ve lost at least 5 kg?

Do not forget the Echo Law: what you don't give in smiles, will greet you in discomfort. Guilty communication is a dangerous style that is usually learnt in the family. It consists of taking advantage of other people and putting blame on them. It involves making the patient feel guilty, in order to try to induce them to do something. The root of this feeling of guilt is “you should have done such a thing and you did not”. It is assumed therefore, that there is a “duty”. In our case: good compliance with medication, do everything possible to get healthy, ask a fit for work note. But in an adult society, we should foremost respect patients’ autonomy. Our duty of beneficence is behind, in general, their right to be autonomous. Therefore, we must change our style: no more culpability unless this guilt has a consciously pursued therapeutic effect, or we are going to promote conversations like this:

Nurse: I don't think it's possible to improve your COPD unless you stop smoking.

Patient: I don't think so and I won't quit as I've told you a thousand times.

Nurse: It is your right, but medicines have a limited effect. You are in charge of your health, but we have to inform you regardless of us feeling bad about it. If you change your mind please come back, we can help you stop smoking.

-

Remember tragic events before establishing a relationship of trust

Are you more recovered from the death of your husband?

How are you coping with your breast cancer diagnosis...?

These questions may be appropriate for a later phase of the consultation, never

at the beginning!

-

Inappropriate curiosity

What happened at the trial?

Are you a Jehovah's Witness?

Are you still drinking?

These questions may also be appropriate for another phase of the interview, but avoid them at the start of the consultation.

Situations Gallery

We will study:

-

The patient with underlying aggression

-

The patient with unrealistic expectations

-

Establishing a relationship with a child as a patient

The patient with underlying aggression

«I am very angry with you».

Analyse the following interview. Abbreviations: I: interviewer; P: patient.

P: I am angry with you. My back hurts and what you prescribed last time doesn't seem to work.

I: I am also annoyed with you. You haven't taken your blood pressure and sugar tablets.

P: So, let's see what we can do because I am worse. Tablets, suppositories... Let's try an injection or an X-ray, or something ...whatever.

I: It doesn't surprise me you are not improving. If you don't do what I say, we won't get anywhere.

P: I do whatever is necessary, but at least try to improve the pain I have here (pointing to her cervical spine). What has been prescribed doesn't work for the pain.

I: Who has told you that is no good for pain? Of course it is for the pain! Who has told you it isn’t?

Comments

-

Which is the main mistake of the professional in this scenario?

The Doctor does not listen. The doctor gets defensive and is unable to hear what the patient is saying. He thinks that if he doesn't answer quickly and firmly, the patient is going to step over and push him around. He responds aggressively to the patient’s aggression.

-

What are patient's expectations?

The patient expresses the wish to receive an injection or an x-ray. However, though this is a somewhat incongruent request (is the pain going to improve by doing an x-ray?). The patient expresses their feeling of not being taken into account. That they would like someone to listen or something to be done. Sometimes behind comments like “do something with me, give me an injection, whatever, but do something to relieve this discomfort”, there is a certain degree of the patient wishing to be treated as an object: “I surrender myself to you as an object for you to fix me”.

-

What does the health professional intend with their interventions?

Primarily, preserve their authority.

-

Is the presenting complaint well defined?

No, it isn't. In fact, you may find lots of additional requests at the end of the consultation: “Please, can I have my repeat prescriptions”, “please look at my ears”, etc...Patients with a certain amount of irritability or hostility often make additional requests as a way of “punishing” the health professional who they feel ignores them.

-

Could you think about an empathic intervention that could improve the atmosphere of the consultation?

You could try, among other things: “I see that you are having a difficult time” or “it must be difficult to cope with this persistent pain”

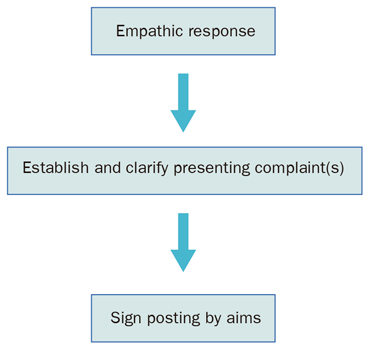

How should the health professional have acted?

They should have:

-

Answered with an empathic statement instead of responded defensively and aggressively.

-

Established the presenting complaint: “what brought you in today? Is there anything else?”.

-

Sign posted by outlining the aims “let's talk about the main topic, how we could get you better?”, “How could we help improve your pain?”.

For example:

P: I am angry with you. My back hurts and what you prescribed last time doesn't seem to work.

I (empathetic response): Oh, I am sorry... (clarifying the presenting complaint) Was this the reason for today's visit?

P: No, I am also here because I am very nervous and I can’t sleep at night.

I (preventing additional requests): Ah, I see, is there anything else?

P: Is this not enough?

I (summarising): If I understand this correctly, you have come today about your back pain, because you’re feeling nervous and because you can't sleep...

P: That's right. I am angry too.

I (sign posting by outlining aims): Let's talk about your main topics, which are improving your pain and your anxiety... how long have you been feeling nervous for?

Remember: Observe the power of this combination:

The patient with unrealistic expectations

Consider the following scene. A patient attends for her first visit with the practice nurse.

What a nice nurse!

P: Ms. Rosa, I am delighted to have you as my nurse because I've heard lots of good things about you. And you know what? I have pains all over my body and nobody seems to get it right. I've seen many doctors, but nobody finds a solution. So, I have joined a relaxation group.

Nurse (reading patient's medical records): Sighing. You have seen very good doctors, and you have received lots of treatments. Chances are that the relaxation group will not work.

P: Oh! Don't tell me that. My neighbour, Mrs. Lockhart, is very happy with her relaxation group. She recommended asking my doctor if I could come and see you. So, here I am, I am completely in your hands.

Nurse: Thank you for trusting me, Mrs. Matilda, but each case is different. From what I am seeing, your case is complicated... I don't have much hope that it will help you...

Comments

-

Does the health professional make any major mistakes in this scenario?

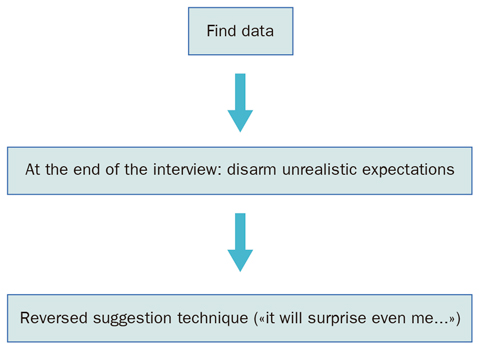

She doesn't make any major mistakes, although it can be improved. From our point of view, the nurse is right not to accept the role of omnipotence that the patient wants to award her. However, she could improve her intervention: it is best to challenge the role of omnipotence that the patient projects at the end of the consultation rather than the beginning. So, at the beginning of the consultation the health professional can concentrate on establishing symptoms and other aspects, without taking into account the patient's praises.

-

The professional throws a prophecy in the sense that 'relaxation therapy sessions may not work'. Is that correct? Or would it be more intelligent to take advantage of the patient’s unrealistic expectations? After all, many healers take advantage of their patients' auto-induced healing power. It is possible that this patient is very impressionable. However, the question is: how long could an auto-induced healing last? Usually only briefly. In addition, the therapist must periodically promote these ideas, which has a significant personal cost. To either suggest or not refute the patient’s expectation that you can perform miracles in the clinical relationship always takes its toll and will invariably lead to disappointment as these expectations cannot be met long term.

-

Where should the professional's efforts be directed?

The Nurse's intervention, reducing expectations, is certainly, an intelligent position. If relaxation therapy does not work, she can always say: 'I thought so'. That disables the vindictive component of many patients suffering from chronic pain: 'you cannot heal me! I had placed so much hope in you''. Such interventions are not possible when we deactivate projections of supremacy: 'I think it will not do anything, but let's try it just in case it helps'. The patient may want to demonstrate their improvement in front of the therapist: 'you said that it would not work and actually I noticed an improvement'. In this case the response could be: 'I'm glad I was wrong, and certainly this is due to you taking this issue very seriously; congratulations'.

How should we act in such situations?

-

Do not either ignore or excessively refute comments from the patient that suggest omnipotence.

-

During the resolutive phase of the interview, moderate patient's expectations: 'your problem doesn't have an easy solution'; or, 'I would be lying if I said I'm going to improve your health quickly; unfortunately there is no miracle treatment, and if you have had discomfort for years, this can take time to improve'.

-

Leave all doors open. For example, 'for now, I think this treatment is suitable for you, but it isn’t always successful the first time. However, we have other treatment options, and may be possible to refer you to another professional. Or try the reversed suggestion technique: “Even I would be surprised if the treatment works for you the first time'.

Let's see these suggestions applied to a patient with chronic pain who also has a somatic and depressive component. In this case, the doctor is finishing their first consultation with this type of patient:

Dr. (disarming unrealistic patient's expectations): Mrs. Matilda, after carefully examining your problem, I realise that you have had this disease for many years. You have been seen by many doctors, and all of them are very good doctors.

P: Yes, it's true.

Dr.: you have received many treatments with little improvement...

P: Yes.

Dr. (reversed suggestion technique): I am going to recommend a treatment, with the best of intentions. But, I don't expect a miracle response. It is more likely that you won't see any relief for the next 20 or 30 days. Then, only gradually, your symptoms will improve.

P (disappointed): oh, ugh!

Dr: Suffering from diseases or conditions which have been present for many years, can only be improved with patience and also with time.

P: I was coming to you with so much hope!

Dr.: I prefer to disappoint you now rather than in a few months. I am going to be very honest with my views, and hopefully you will value this.

P: I agree with this.

Remember: Patient imputes omnipotence

Establishing a relationship with a child as a patient

Let's move to a paediatrician's consultation.

Something is happening to this child!

Mother: I am bringing Alex (8 years old) as he must have a cold or something, because he is not himself.

Doctor (addressing the boy pleasantly): Alex, do you have a cold?

The child nods and smiles a little shy.

Mother: He is off and I thought, 'this is not normal', and my mother in-law said: 'take him to the doctor as there is a very strong flu going around...'

Doctor (interrupting): Did you check his temperature with a thermometer?

Mother: We had one of those automatic thermometers that are placed in the ear, but I think it doesn't work because it always shows 36.

Doctor : Do you have a sore throat, Alex?

The child says no moving his head and looks at his mother laughing.

Doctor : Come to the examination couch, I would like to examine you.

Comments

-

Does the health professional make any mistakes in this scene?

In this scene, it appears that the doctor agrees that Alex has a cold. However, the mother actually comes in as Alex 'is not himself' and the cold seems to be the grandmother's idea. Accordingly, the doctor will do a physical examination to confirm the idea of an upper respiratory tract infection, when in fact the history taking data is poor. It may happen that he finds an inflamed throat and he applies the 'one plus one law': 'a fact from the history that points me to X, corroborated by an examination finding which concludes, certainly has X'. To his surprise the interview can take the following turn:

Doctor: Well in fact, I can see he has an inflamed throat. There is currently having a viral bug going around....

Mother: Could this be the reason why Alex feels so tired?

Doctor: Well, maybe. He doesn't have a fever, but maybe...

Mother (interrupting): Please note that he has been feeling tired for a month and a half.

Doctor: A month and a half? You didn't say that...

Mother: That's what I was trying to say. My child has changed from a couple of months ago. He has always been a fidgety child even his teacher has noticed he has changed.

-

How can the doctor reverse the mother's rhetorical style?

This can be done with a good history of the presenting complaint. Clarifying the adjectives the mother uses to describe the child's condition, and considering the list of present complaints which will then be compared with the child himself. This would allow the doctor to make a focused examination directed at the patient's fatigue symptoms.

-

Does the doctor know how to talk to the child?

In this short fragment of the interview, he approaches the child in a friendly way, trying to confirm, disprove or expand what his mother says. However, it is likely that his effort is in vain, because while the mother talks, the child will be basically quiet, in a complementary role.

How should we act in such situations?

To make the child talk, we must create his own space. For example, taking the opportunity of him being away from his mother while in the examination bed. In this case, it may be convenient to initiate a dialogue related to his activities (recreational or academic). This will gradually lead us to our goal. For example:

Doctor: How are guitar lessons going? Because I know you play the guitar, don't you?

The boy shrugs.

Doctor: I think he doesn't like the guitar.

Mother: Yes, he likes it doctor.

Doctor: No, he doesn't like it, does he? (with one hand on his head the doctor makes him say 'no'). You see, you don't like it.

Alex(laughing): Yes, I do like it!

Doctor: What days are you having guitar lessons?

Alex: Thursdays, after finishing school.

Doctor: when you are at home, do you prefer practising your guitar or watching TV?

Alex (laughing): watching TV, I like the X factor.

After a few more questions a sleep disorder linked to a chaotic and permissive schedule emerges.

|

Remember:

|

Advanced Concepts

Comfortable working

The comfort of health care professionals should be considered a public health matter.

Feeling physically and mentally well while we listen and analyse our patients' problems has a direct impact on our communication and data gathering and on our successes and mistakes.

Each of us is primarily responsible for our own comfort. Find a brief list of factors to be controlled below:

The Time range for the duration of patient appointments

Tip: try to get an agenda to establish a reasonable balance between waiting time for patients and the workload they generate. 'Smart agenda' concept: an agenda that automatically assigns a realistic appointment time for the patient according to their profile. Young patients with low demands may have a 7 minute appointment, while elderly patients over 75 years old hardly ever require less than 15 minutes. If your software does not have 'smart agenda', this could be solved by giving similar instructions to the administrative staff. For example: 'for patients over a certain age, non English speaking and first appointments always give 15 minutes', etc. We recommend the 'accordion' agenda system: 3 or 4 slots of 5 minute appointments, followed by an unallocated time of 10 to 15 minutes. This way you are not inactive if a patient doesn't attend, and you can lengthen any of the previous appointment slots if required (Borrell F, 2001; Casajuana J, 2000; Ruiz Téllez A., 2001).

The amount of administration work which must be assumed within the clinic

Tip: Endeavour to allocate a separate time period for sick notes and repeat medication prescriptions from patients' appointments. Try giving responsibility for the administrative side of these to the administration team (Casajuana J., 2003).

Order on the desk: print outs, prescriptions, etc.

Tip: Have a system of trays or dividers. The fewer objects there are on the desk, the better. If you use a computer always put it on one side, to avoid anything standing between you and the patient.

Interruptions: External calls, staff, other patients ...

Tip: Train the administration staff to triage phone calls and request that they only put through to you those that are urgent or from certain people. Queries from patients can be added to the 'telephone consultation' list. In this case, the health professional calls the patient at an appropriate time slot.

Comfort should also be pursued during the consultation. Here you can find some standards:

-

Take care of your physical wellness. A chair with wheels, a land line telephone, a computer with an internet connection, access to tea and coffee, etc.

-

Try to alleviate cravings and avoid the typical mid-morning hypoglycaemia (this is almost always the result of a very quick breakfast).

-

Ventilate the room properly.

-

Analyse the environment of your room and propose any necessary changes: air conditioning, light, decoration...

-

Have all the necessary clinical material in your room. Ask for it! Don't wait for your practice manager to find out your needs, they may be very busy. If you don't get a response to asking verbally, make a written request.

-

There must be sufficient, but not too many people present during the consultation for the consultation to succeed. Sensitively, but firmly request that any unnecessary third parties wait outside the room. Or conversely: invite others not present into the consultation room.

-

Don't think you need to dedicate an indefinite amount of time to each patient. You must look after all your patients, which means occasionally having to advise a patient: 'I am sorry, but I cannot spend any more time on this at the moment. How about if we discuss this matter when...'.

Basic habits of interviewing

Read any previous medical records, a friendly greeting and defining the present complaint(s).

With these basic ideas, we are ready to study the deep structure of an interview.

The rational-emotive model. Fundamentals

The first statement of this model is that the interview is divided into two phases: the exploratory and the resolutive. The exploratory phase of the interview brings all the clinician’s actions together to establish an idea of the patient's condition (problems, state of health, diagnoses), as well as strategies to help.

When does the exploratory phase end and the resolutive phase start? At the time the interviewer makes a diagnosis or proposes a plan or gives advice, the resolutive phase starts. Consider what happens in the exploratory part.

The exploratory part of the interview begins with a stimulating situation. A patient enters into the room with a big smile, or complaining with signs of intense anxiety or we find them passed out on the street. These are all different stimulating situations. Each stimulating situation leads to a different frame of the interview. The frame, or intentionality, of the interview (we use both terms as synonymous), is to answer the following question: 'what's expected of me?' The answer we give, for example, 'he wants something for the cold', 'he wants a plan to stop smoking', etc., is the intentionality or frame of the interview.

Some studies show that in the first few minutes of the interview, the health professional has imagined the whole sequence of actions that will take place, including the possible drug he will prescribe. It happens in a manner such as:

Patient (young, good health): 'You can't imagine how much I cough. I don't have a fever, but I can't work with this cough!

Doctor (thinking in a split second: 'it looks like a dry cough, viral type, cough syrup X will work well. This patient must come in primarily for a sick note and some symptomatic relief. I will take a quick history and briefly auscultate their chest, if there aren't any abnormal findings, I will prescribe cough syrup X): How long have you been coughing?... Have you had a fever?... Are you bringing up any sputum?... Could you come to the examination couch, please?

Under the term 'exploratory behaviour' we mean all the questions or physical examination manoeuvres that are intended to confirm or disprove a hypothesis

formed in our head. For example: 'if this patient has sinusitis, I should find nasal discharge, pain in the sinus area and tender sinus points', says the clinician. You are applying a decision rule (or heuristic) type: 'if I find this data I will close the interview by recommending that the patient take such and such medication'.

However, it may be that new data from the patient refutes the early hypothesis we had set. In this case, the interview must be reframed:

Doctor (thinking to himself): There aren’t any examination findings to confirm that this patient has a cold. I will recommend paracetamol and I will keep listen and see if another complaint appears at the end of the interview which actually justifies this visit.

Therefore, what is reframing the interview? It occurs when we realise we were going through the wrong path: the patient wants something different from what they said they wanted or from we understood they wanted. Or their problem is of a different nature than initially we understood. For example, a 12 year old boy who complained about acute abdominal pain, initially diagnosed as gastroenteritis. However, the pattern of the pain which lasts about 10 'overwhelming' minutes, is colicky in nature and is associated with feeling hot in the face and chest, and which occurs for example, before going to school, guides us towards an atypically presented panic attack. At this point we 'reframe' the interview.

What's the difference between type 1 and type 2 reframing (Figure 1.4)? Type 1 occurs when we rethink the early hypothesis. Type 2 reframing requires us to rethink the general framework of the entire interview and involves scheduling another appointment time to deal with the case.

To make things a little clearer with some examples:

-

Type 1 reframing: 'no, he doesn't have a cold, actually he has sinusitis'.

-

Type 2 reframing: 'I thought this patient came in with a cold, but actually he comes to discuss his marital problems. If I go into this topic, it will take me at least half an hour'.

-

Type 1 reframing: 'this agitated 80 year old patient who has dementia, doesn't allow his family to have a good night’s sleep. Maybe I should think about increasing his sedative medication at night time.

-

Type 2 reframing: 'what if the problem is not because the patient doesn't sleep at night time? Maybe the problem is due to a lack of a permanent carer that knows the patient well. I must ask the family'.

The main obstacle for a type 1 reframing is disproving some diagnostic hypothesis we took to be almost certain. The difficulty for type 2 reframing is even greater: what we were trying to solve was not what the patient wanted, or was not what we have interpreted, or was not the right thing for the clinical situation. Type 2 reframing is more difficult because we had already decided 'what the patient had or what the patient wanted'. We had made a forecast of time ('now I am going to close the interview'). Type 2 reframing always implies a reallocation of time and therefore requires redesigning the consultation. We discovered that the patient actually 'wanted something else'. For example, if a patient comes in with dizziness, and only towards the end of the interview he shares that he has a problem at work, the health professional may have the following inner dialogue: 'wow, it turns out that this dizziness is not caused by anaemia or an ear problem, but due to bullying at work...but now I don't have time to address it!'.

Cordial or empathetic? The importance of welcoming the patient

The way we accommodate the patient, even if it is their thirty-second time coming to see us, always has great importance. We suggest surface qualities of the interviewer should be warmth (emotional tone of pleasure), respect (they have every right to be or think as they do) and friendliness (by which we mean that the person is welcome, and they feel good talking to you), among others. Deep qualities would be empathy (knowing how to put yourself in the patients' shoes), emotional restraint (showing active listening without being forced to 'provide solutions to everything'), and assertiveness (knowing at all times the direction the consultation must follow), among others. The tone and pitch of voice is important when transmitting these qualities. But there are communication barriers for this: everything that makes us different to the patient will act as a barrier (educational level, age, sex, appearance...), some clinical situations (very urgent matters, difficulty hearing or other expressive or understanding difficulties...), and most frequently, the fact of having to make a diagnosis. Let's study this last point in greater detail.

The rational-emotive model indicates that in the exploratory phase much of the emotional stress builds up. We don't know what to do or what happens to the patient. And just at this time we are asked to be cordial when we are concentrating so hard!

To alleviate this paradox as far as possible, we recommend using some cordiality markers, which are basically: a smile when we welcome the patient, shaking hands, mentioning their name, eye contact... Making these gestures a habit, is the challenge. And giving control to the patient. A patient admitted to ICU described when the staff were manipulating his body without him knowing what they wanted with it (even if it was only to wash him) as 'the worst days'.

Don't be influenced by the discussions in the waiting room, and try not to take part in them. You will notice that even though a patient is angry about the waiting time, once he gets into the consultation he soothes, now his consultation has started, his interest lies, (as does yours), in you making your best attempt at solving his presenting problem. Therefore, don't justify the appointment system or discuss the order of patients. This task is the responsibility of the administration staff of the practice.

Returning to the subject line: Is more important being empathetic than cordial? Is it preferable an interviewer that is in tune with the deep emotions of their patients, when they emerge or an interviewer that melts in hugs and greetings, but avoids empathetic approaches of the sadness, suffering or pain? In general we could say yes, because the lack of empathy leads the patient to feel undervalued. However, we should emphasise that if a minimum level of kindness (and patience) isn’t present, there won't be opportunities for empathy. For patients to reveal their deeper emotions, we must give prior doses of warmth, something like: 'you can feel as if you were at your home', ' whatever you tell me will be well received and treated with the maximum respect and confidentiality'.

Don't forget that if you are forced to reframe the interview, the emotional effort to do this will make you less warm and empathetic. Another challenge to overcome!

Overwhelmed

Are you overwhelmed? If your answer is yes, you may be interested in reading this section.

Let's start with a shocking statement: sometimes being overwhelmed is the perfect excuse to justify our lack of professional ambition. Every time we are overwhelmed... we can't do things better! We give 'everything we can and more'...

One wonders openly and honestly: where does this overwhelming feeling come from? To what extent have I created this feeling of being overwhelmed myself? Here are some 'tricks against this overwhelming feeling':

-

Overwhelmed due to poor planning of your activities

In this case there are excessive environmental and external pressures: patients’ appointments every five minutes, interruptions, emergency patients added to patients already waiting for their visit... The solution is to set realistic intervals between appointments and an adequate workload, as we noted before.

- Burden originating from the lack of emotional control

Negative emotional impacts may create a dazed feeling in the health professional, which will lead to them practicing a superficial thinking style. The health professional gets into their office scared. They will try to do their work in a hurry, without delving into the different clinical pictures. 'I'm overwhelmed, I'm overwhelmed,' he says. So, he is increasingly overwhelmed. He doesn't allow himself to reflect on the reality. Herein lies the key theme of this topic: against feeling overwhelmed, concrete reflection of the specific clinical situation. Focus on each moment (and enjoy what you do).

-

Burden originated by slow decision-making

For some interviewers every decision is a long and complex reflexive act. In

such cases, if the professional doesn't have an automated a series of basic routines that ease thinking each and every step, fatigue is going to be huge, and at the end they could not avoid distractions. The priority must be, therefore, to automate decisions against well-defined clinical settings. For example, 'all patients who have an unexplained cough for over one month will require a chest X-ray'. This is called building our own 'situations library'.

However, we insist on the initial idea: feeling overwhelmed can (or may) be an emotional habit. When that happens it is impossible enjoy the work, smile in a relaxed manner and make jokes with the patient. The only thought is 'I have to do this', 'I must finish before this time', 'they call for greater performance', etc. When that happens there is no capacity for genuine responses. There is only capacity for planned answers and answers that suit our role. Actually, we are not fully into the situation, it is only part of us that 'must resolve' the situation. We leave behind our sense of humour, curiosity, and the ability to surprise and even learn from the patient... A good daily exercise to do before and during the consultation is to ask ourselves: what can I do to enjoy this time? What makes me overwhelmed? What irritates me?

Preventing additional requests

Precisely, an aspect that can lead to feeling overwhelmed by feeling irritated is what we call 'additional requests' at the end of the interview. The common 'while I am here, why don't you take a look at my back too?' These demands put out the best time plans and force us to do type 2 reframing, which demands a bigger emotional effort. Find below what the interviewer thinks:

- Ugh! If I say there is no time, I could jeopardise the good rapport I have built up with this patient, but if I re-open the interview I am going to run late and patients will need to wait.

For this reason we recommend a good definition of the present complaint, and if we suspect that a patient will have 'many different complaints' insist on asking... 'is there anything else?'. Although, we will always find patients who will say 'as I am here' say at the end of the consultation. In such cases:

-

Do not reproach. It is not worth it. You won't change the healthcare reality. On the other hand, you could jeopardise your doctor-patient relationship.

-

Decide quickly if you are going to address or postpone the demand. If you decide to reopen the interview, do it promptly: it will save you time. And if you decide to postpone the demand, use the following statement: 'What you are saying requires another appointment. You don't deserve less. But, I can't offer you the time this issue needs now. Can we book an appointment for next week and we will discuss this in further detail?'

It is important to distinguish between when a patient adds reason for consultation at the end of the interview because of embarrassment, and when they are ‘going shopping' and are adding requests obtain the maximum benefit for the time they have invested in attending the appointment.

Recognising negative emotions

Feeling overwhelmed is one type of negative emotion, but there is more, of course.

Firstly, when we start our clinical day we are immersed in an emotional state. If at this key moment of the day we think:

-

I'm tired and overwhelmed. I have to finish the clinic as quickly as I possibly can and go home.

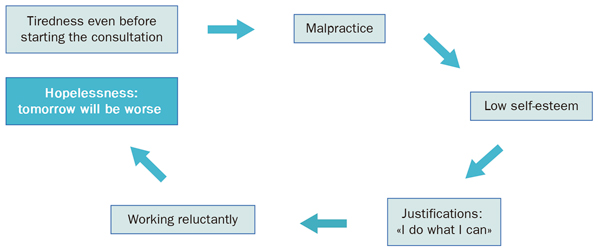

In this case we will have succumbed to a negative emotional state which is clearly dangerous. The fact that we are working poorly, knowing that we are performing below our optimum, lowers our self-esteem and enters a vicious cycle as illustrated in Figure 1.5.

|

|

Figure 1.5. The circle of learned helplessness |

Negative emotions we get from patients may also lead to discouragement and low self esteem. There is an emotional generalisation effect by which we conduct bad vibes from a single concrete patient to the whole group of patients. The first two visits may have worked well, but third and forth may be unpleasant (one patient complaining without reason, another blames us...). We think, 'what have I done today for patients to treat me this way?' It is an irrational thought, but it exists. We may respond, at the height of magical and irrational thinking: 'so, from now I won't be so nice to 'them', they will see who I am'. Therefore, we can distinguish two types of interviewers:

-

Those who are led by patients' emotions of and practice 'eye for an eye': They respond to hostility with hostility, disaffection with disaffection, etc. We describe them as having a reactive emotional style, as they react similarly to the stimulus received.

-

Those who set the emotional tone of the consultation, without being carried away by the receiving negative emotions. We call this a proactive style.

Example: with a humorous tone, seeking patient's complicity: 'Could you see you feel better? You are even able to laugh a little'. Or with a hostile patient: 'Let's see how we can help you', while we smile cordially.

The proactive interviewer not only grows in the status of their population, but they know how to preserve their self-esteem. This is more important than knowing a certain communication skill.

The importance of a good doctor-patient relationship

Since the mid-eighties, the need for health professionals to adopt an illness and patient health-centred experience has been stressed. This orientation is called the 'patient-centred model' (see Table 1.5)

|

Table 1.5. Model focused on the patient or client. Definition

It is a relationship where the interviewer or health professional promotes a co-operative relationship where both protagonists find a common ground for addressing the patient's concerns, the decisions to be made, the patient's ideas about what is happening and their expectations. Decisions concerning what to do, taking into account the patient's personal and cultural expectations of illness, while the patient is still a member of a community. |

|

Source: Lewin SS, 2001. Tizon J., 1989. |

Some evidence seems to support this model. It seems that interviewers who work more on patients' interests and expectations achieve better satisfaction from them (Steward M, 1999). Some other works insist on the benefits of clarifying patients' demands (Holman H, 2000). Generally, when the interviewer and patient reach an agreement on the meaning of the symptoms and their treatment, there is better patient satisfaction, and functional (mobility, activity) and biomedical outcomes improve (Bass MJ, 1986; Henbest RJ, 1999; Starfield B, 1981). Interviewers with a participative style in decision making, have more satisfied patients, and patients change doctor less (SH Kaplan, 1995). In addition, to support the proactive style, it should be noted that an 'optimistic' doctor can get up to 25% more satisfaction from patients compared to a more pessimistic one, for the same medical condition and giving the same treatment (Moerman DE, 2002). In a study with physiotherapists, the non-verbal communication (smiling and expressing facial emotions in a more generic way), was related to better health outcomes at three months of observation (Ambady N, 2002). This therapeutic function of the relationship was already known by Balint (Balint M, 1961). In conclusion, a professional's participative style is related to better control of chronic diseases (Greenfield S, 1988, 1985), but there is no agreement on whether this control leads to better results on indicators of health outcomes (N Mead, 2002).

More sceptical researchers doubt about whether and the extent to which it is possible to develop a patient-centred consultation style (see Table 1.6), and ascertain all the patient's worries and concerns. Thus, for example:

-

Torio (Torio J, 1997, a, b, c) finds that Andalusian patients don't prefer this style.

-

Bartz (Bartz R, 1999) Warns that doctors who believe they are 'patient-centred', actually are not at all.

-

Marvel (Marvel MK, 1999) found that doctors redirect the direction of the interview before the patient has been able to express all their concerns.

-

Braddock (Braddock CH, 1997) finds that only 9% of visits have an informed decision making process. A hermeneutic analysis during the decision making process shows the subtle, but powerful use of language by the health professional, either by introducing new terminology or mastering discussion subject (Gwyn R, 1999). There are no dialogues with equal power.

|

Table 1.6. Patient-centred relationship: operating characteristics |

|

|

(SM Putnam, 1995) |

How do patients perceive doctors?

Jovells A. (2002, 2003) conducted a qualitative study (six groups of about 8 or 9 participants from different locations in Spain) which shows the following picture:

-

Patients complain basically about the long waiting times.

-

They have a good perception of the general practitioner when there is some continuity. However, lack of interest is noticeable when there are not enough regular appointments by the same doctor.

-

They have a perception of high professional competence.

-

Women are more active in seeking information.

-

There is a demand for information, but related to the specific disease one suffers. In some cases there is ambivalence about 'knowing or not knowing' the truth.

-

Doctors are considered the most reliable source of information, followed by pharmacists. Nurses were seen as good professionals, who offered support and care.

Among other testimonies we want to highlight:

-

'The first thing one expects from a doctor is eye contact, active listening and satisfactory answers after the patient has explained their symptoms. It is also expected that the doctor prescribes a treatment and recommends regular follow ups'.

-

'When you get information from a health professional, it should be understandable. Sometimes the health professional talks, talks and talks... and as a patient you think: ' he must believe that he is next to a colleague at university while studying medicine!'

In relation to nursing there is a study from De Haro-Fernandez (2002) that, in summary, says that in a hospital setting, only 43% of patients were able to distinguish nurses from other health professionals. However, their relation and communication tasks were well valued. But, it was felt that they were in a hurry (37.5%) and inappropriate comments were produced continuously (13%), with a deficit in information prior to hospital discharge (only 48% of respondents understood the information clearly, in a useful way and were given sufficient information).

Therefore, here are some challenges for the 21st century:

-

We must create a 'friendly' environment where clinical relationship can develop, with adequate time and resources. Having about 10 minutes on average per patient seems a reasonable minimum, even if limited.

-

The challenge is not always the 'paternalistic' approach (always so criticised), but a cold and technical relationship, lacking empathy and rushed.

-

The organisation and payment method should encourage and be personalised to professionals. It should reward professionals who care for difficult patients, immigrants or patients with special needs.

-

The impact on the team's life of the individual profile of each doctor or nurse has been poorly studied, but in our opinion it is very important. Each team creates an ethos, values which are visible to the patient. If these values are misaligned, the clinical relationship will have a defensive, irritable or authoritarian component, in line with what some citizens expect from us (this is what some authors have called transference against the group [Bofill P, 1999, Blight J, 1992]).

Bibliography

Abadi N, Koo J, Rosenthal R, Winograd CH. Physical therapists’ nonverbal communication predicts geriatric patients’ health outcomes. Psychology and Aging 2002; 17(3): 443-452.

Balint M. El médico, el paciente y la enfermedad. Buenos Aires: Ed. Libros Básicos, 1961.

Bartz R. Beyond the Biopsychosocial model. New approaches to Doctor-patient interactions. J Fam Prac 1999; 48(8): 601-607.

Bass MJ, Buck C, Turner L. The physician’s actions and the outcome of illness. J Fam Prac 1986;23: 43-47.

Bofill P, Folch-Mateu P. Problemes cliniques et techniques du contre-transfert. Rev Fran Psychanal 1999; 27: 31-130.

Borrell F. Agendas para disfrutarlas. Diez minutos por paciente en agendas flexibles. Aten Primaria 2001; 27(5): 343-345.

Braddock CH, Fihn SD, Levinson W, Jonsen AR, Pearlman RA. How doctors and patients discuss routine clinical decisions. Informed decision making in the outpatient setting. J Gen Intern Med 1997; 12(6): 339-345.

Casajuana J. La gestión de la consulta. En: Curso a distancia Gestión del día a día en el EAP. Módulo 1: págs. 61-76. Barcelona: semFYC, 2002.

Casajuana J, Bellón JA. La gestión de la consulta en atención primaria. En: Martín Zurro A, Cano

Pérez JF. Atención Primaria (5.a edición) Madrid: Ed. Hartcourt S.A., 2003 (en prensa).

Cohen-Cole SA. The Medical Interview: the three-function approach. Sant Louis: Mosby, 1991.

De Haro-Fernández F, Blanca Martínez-López M. Instrumentalizar la comunicación en la relación enfermera-paciente como aval de calidad. Rev Calidad Asistencial; 2002, 17(8): 613-618.

Gwyn R, Elwin G. When is a shared decision not (quite) a shared decision? Negotiating preferences in a general practice encounter. Soc Sci Med 1999; 49: 437-447.

Henbest RJ, Stewart MA. Patient centeredness in the consultation. 2. Does it really make a difference? Family Practice 1990; 7: 28-33.

Holman H, Lorig K. Patients as partners in managing chronic disease. Partnership is a prerequisite for effective and efficient health care. BMJ 2000; 320(7234): 526-527.

Greenfield S, Kaplan SH, Ware JE, Jr., Yano EM, Frank HJ. Patients’ participation in medical care: effects on blood sugar control and quality of life in diabetes. J Gen Intern Med 1988; 3: 448-457.

Greenfield S, Kaplan S, Ware JE, Jr. Expanding patient involvement in care. Effects on patient outcomes. Ann Intern Med 1985; 102(4): 520-528.

Jovell A. El Proyecto del paciente del futuro. Proyecto Internacional. Investigación basada en entre- vistas en grupos en España. Julio 2001. Presentado en: Fundación Biblioteca Josep Laporte, MSD, Seminario: El paciente español del futuro. La democratización pendiente. Lanzarote, 5 Octubre 2002.

Jovell A. El paciente «impaciente». ¿Gobernarán los ciudadanos los sistemas sanitarios? El Médico, 25/4/2003: 66-72.

Kaplan SH, Greenfield S, Ware JE, Jr. Assessing the effects of physician-patient interactions on the outcomes of chronic disease [fe de erratas en Med Care 1989 Jul; 27(7): 679]. Medical Care 1989;27: S110-S127.

Kaplan SH, Gandek B, Greenfield S, Rogers W, Ware JE. Patient and visit characteristics related to physicians’ participatory decision-making style. Results from the Medical Outcomes Study. Med Care 1995; 33(12): 1.176-1.187.

Lewin SS, Skea ZC, Entwistle V, Dick J, Zwarenstein M. Interventions for providers to promote a patient-centered approach in clinical consultations. Cochrane Library [4]. Oxford, Update Software,

2001.

Marvel MK, Epstein RM, Flowers K, Beckman HB. Soliciting the patient’s agenda: Have we impro- ved? Jama 1999; 281(3): 283-287.

Mead N, Bower P. Patient-centred consultations and outcomes in primary care: a review of the literature. Patient Educ Couns 2002 Sep; 48(1): 51-61.

Moerman DE, Jonas WB. Deconstructing the placebo effect and finding the meaning response. Ann Intern Med 2002; 136(6): 471-476.

Neighbour R. The Inner Consultation. Lancaster: MTP Press, 1989.

Putnam SS, Lipkin M. The Patient-Centered Interview: research support. En: Lipkin M, Putnam SM, Lazare A. The Medical Interview. New York: Springer-Verlag, 1995.

Ruiz Téllez A. La demanda y la agenda de calidad. Barcelona: Ed. Instituto @pCOM, 2001.

Starfield B, Wray C, Hess K, Gross R, Birk PS, D’Lugoff BC. The influence of patient-practitioner agreement on outcome of care. Am J Public Health 1981; 71: 127-131.

Stewart M, Brown JB, Boon H, Galajda J, Meredith L, Sangster M. Evidence on patient-doctor com- munication. Cancer Prev Control 1999; 3(1): 25-30.

Tizón J. Componentes psicológicos de la práctica médica. Barcelona: Doyma, 1989.

Tizón J. Atención Primaria en Salud Mental y Salud Mental en Atención Primaria. Barcelona: Doyma, 1992.

Torío J, García MC. Relación médico-paciente y entrevista clínica (I): opinión y preferencias de los usuarios. Atención Primaria 1997; 19(1): 44-60 a.

Torío J, García MC. Relación médico-paciente y entrevista clínica (II): opinión y preferencias de los usuarios. Atención Primaria 1997; 19(1): 63-74 b.

Torío J, García MC. Valoración de la orientación al paciente en las consultas médicas de atención primaria. Atención Primaria 1997; 20(1): 45-55 c.